Australian Federal Budget Speeches, and Why You Should Care About Them

When budget time comes around, I book myself out of my evening parenting duties, and put the ‘do not disturb’ sign on the door. I tune in for the broadcast of the budget speech, while browsing the net, waiting to see when the transcript is released. Since taking up this new hobby, I am more and more convinced that the Australian Federal budget speech is the closest thing Australians have to the American State of the Union (or ‘SOTU’).

There are obvious differences: SOTU is given by the head of the executive branch of government, while the budget speech is given by our Treasurer. America is a considerably bigger polity, where voting is optional.

But the similarities are just as important. Like the SOTU, the Australian Federal budget speech is an annual speech, given at a specified time in the political cycle. But most important in my comparison is the scope of the budget speech. The budget speech typically gives us a picture of the standard measures of the health of the economy. In addition, given that the speech accompanies the government’s decisions on how and why it raises revenue through tax, and why and on what it spends our taxes, its purview is quite grand.

In fact, there is no more concerted action by an incumbent Australian government in a given year than that taken in the presentation of a budget. Consider for a moment that the estimated total revenue for the 2015-16 financial year is close to $400 billion. The budget is relevant to all aspects of our lives.

In a book titled Deeds done in words: Presidential rhetoric and the genres of governance, Campbell and Jamieson argue that the State of the Union puts American presidents “in the role of national historian” and that “more eloquent presidents have seized the opportunity to reshape reality and to imprint that conception on the nation”.

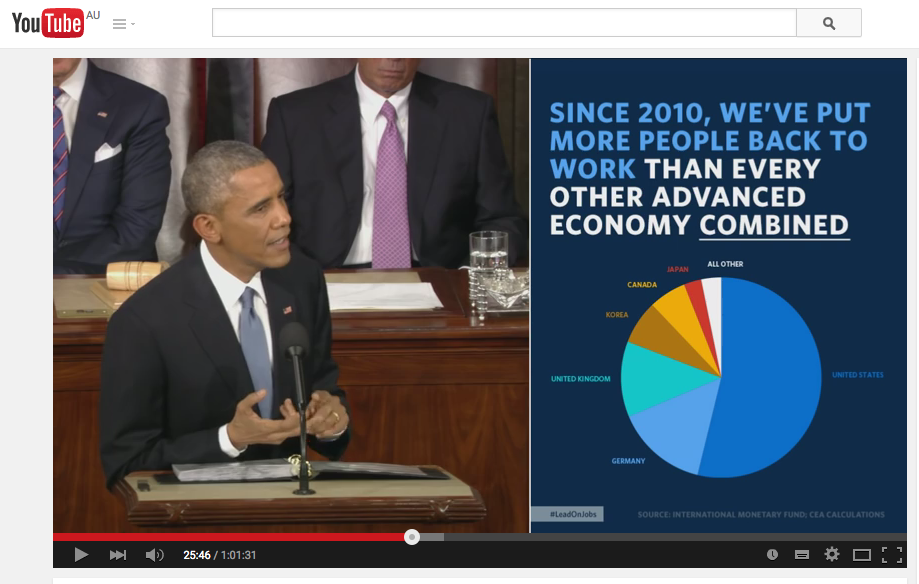

The Federal budget speech, perhaps a mere country cousin to the flashy American version (you can watch the latest one here, with all of Obama’s infographics) is none-the-less about where we are, and where the government believes – or says it believes – it is taking us.

In January this year, 31 million Americans tuned into Obama’s 2015 State of the Union address. This was well down from the audience the President pulled in his first year in the Oval Office, when 52 million watched the speech. At the peak of his belligerence, George W. Bush drew an audience of over 60 million. Clinton’s top performance, in his first year as President, was over 66 million. The consumer information and research company, Neilson has published all the viewing figures for the State of the Union back to the start of Clinton’s presidency.

Even in the bad years, this degree of public interest in a presidential speech looks astonishing from down under. I can’t find any figures or even interest in how many Australians watch the Federal budget speech.

The public’s interest in America is matched by the academic attention to presidential rhetoric in America. As Dennis Grube in the Institute for Social Change at UTAS has written, America has a “vast and growing scholarship on rhetoric and leadership in the field of US presidential studies”. By contrast, Grube continues, in Westminster jurisdictions like Britain and Australia, political rhetoric is largely neglected.

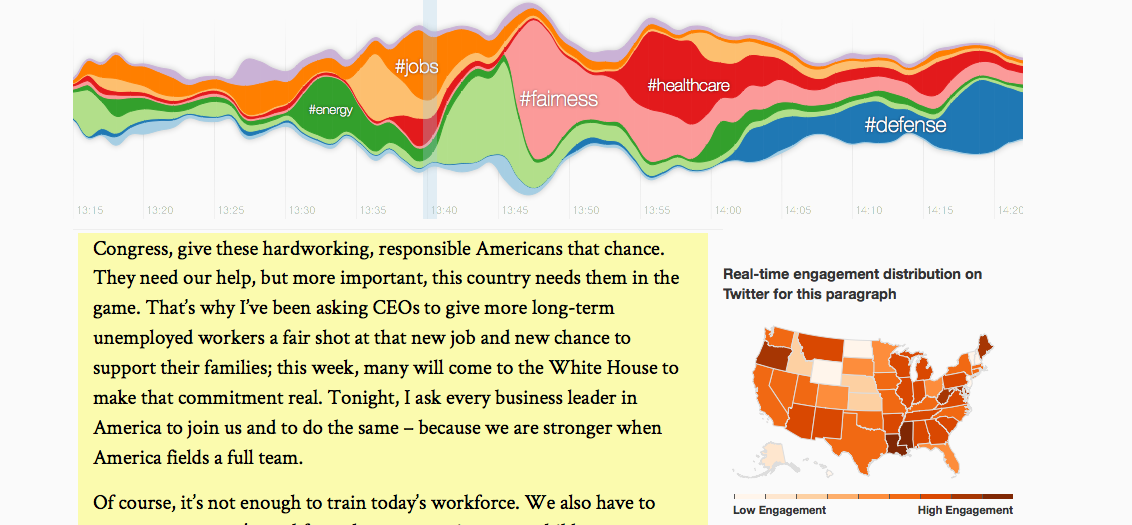

Websites archiving American presidential discourse abound. You can also find some great visualizations of SOTU speeches. Twitter published this last year, an interactive visualization of the topical preoccupations of tweets with the hashtag #SOTU2014 as Obama’s speech unfolded. It even shows the degree of engagement on Twitter by states: Louisiana, Tennessee and Alabama sparkle when jobs are the major topic. “Fairness” had low engagement in Wyoming and Montana, but was very high in many other states.

The Atlantic magazine this year produced an animation they called “Mapping the State of the Union”. It shows all the locations, by year, to which American presidents have referred in the State of the Union addresses.

In 2014, The Guardian, one of the leaders in “data journalism”, ran all the speeches to that date through the Flesch-Kincaid readability test, a widely used and deeply flawed measure of “reading level”. The newspaper’s headline for the beautiful graphic of their findings reads “The state of our union is … dumber”, and their subheading lamented the declining “linguistic standard” (whatever that means) of the SOTU.

The obvious alternative interpretation is that contemporary American speech makers strive for a broader, more diverse, audience. Arguably, this makes the speeches of the modern era more, not less, complex, even if average word or sentence length has declined.

More wonderful still than these resources for the study of the SOTU is Brad Borevitz’s State of the Union website.

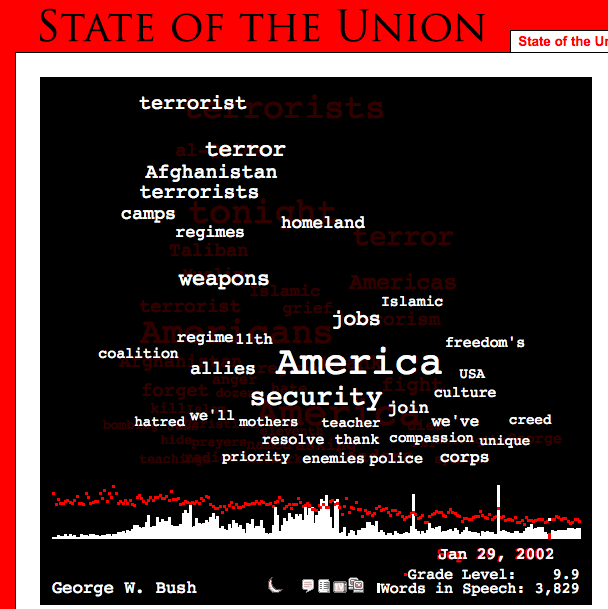

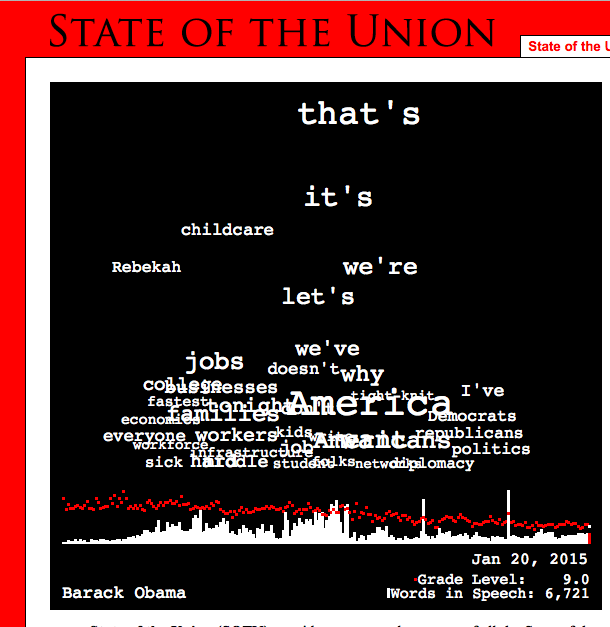

Borevitz has a complete corpus of all SOTU speeches from 1790-2015. Drawing on standard coding, his website allows you to examine the most frequent words in a speech (the top 40), along one axis, and their ‘average position’ in the document along the x axis. Here’s a snap comparing the top frequencies of Bush’s 2002 ‘axis of evil’ speech with Obama’s 2015 speech.

| BUSH 2002 (Axis of Evil speech) | OBAMA 2015 |

|

|

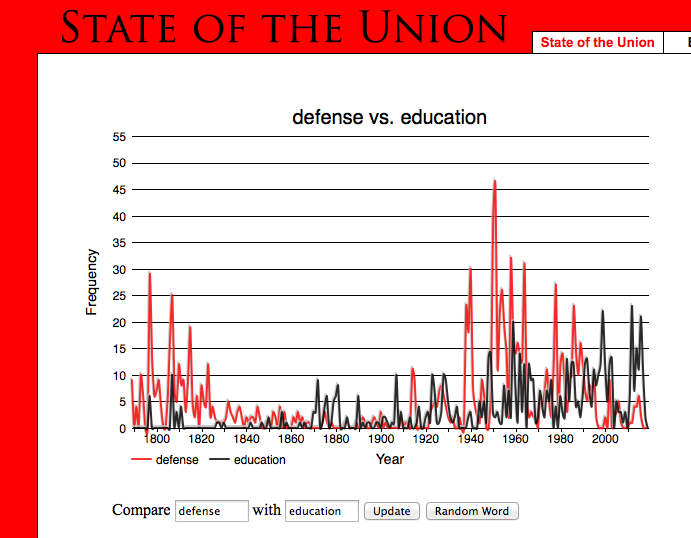

You can also search the entire corpus for particular words, or you can compare words. As the graph below shows, American presidents are much more preoccupied with ‘defence’ than with ‘education’.

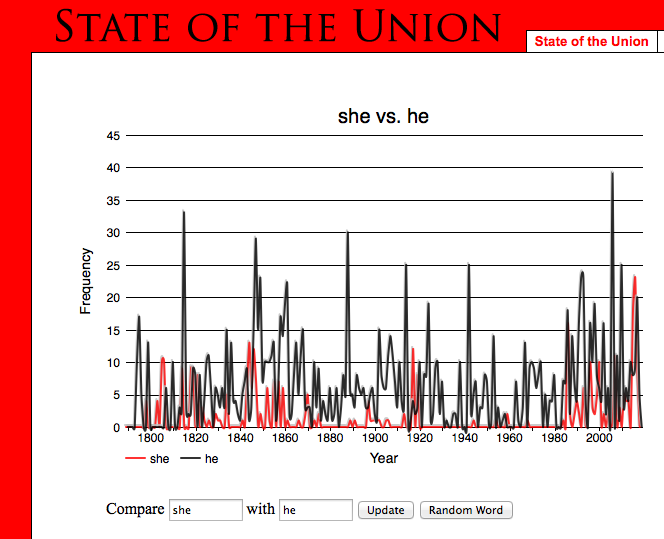

If pronouns are any measure, then the protagonists in a SOTU address are overwhelmingly male.

I now have the previous 35 Federal budget speeches at my finger tips – a corpus stretching back to Howard’s time as Treasurer. Using a standard concordance programme, it is a simple matter to check, for instance, how many Treasurers have considered mental health worthy of a mention in the budget speech (three so far: Willis, Costello, and Swan). Or how often ‘terrorism’ is mentioned (Costello, in every speech from 2007-2012; and Hockey in his 2015 speech) compared with attention to domestic violence (only once in Costello’s 2004 budget speech).

Many of my friends and family despair of our politicians. And in each election campaign, commentators lament the passing of the good old days, when there was ‘real debate’ and not just spin. Over 2000 years ago, Rome’s greatest orator, Cicero, wondered whether “men (sic) and communities have received more good or evil from oratory and a consuming devotion to eloquence”. He firmly believed in the social good that can come from eloquence, though only when combined with wisdom.

Among the many powers of eloquence, Cicero argued, was that it was the only means to induce “one who had great physical strength to submit to justice without violence”.

Is it absurd to suggest that more Australians should take the Federal budget speech seriously? If the budget speech attracted a real audience of “the people” and if it was the object of serious scholarship, could we collectively raise expectations of how the government argued for its agenda, and explained its decisions about how it spends our billions of dollars of common wealth? Could we bring about stronger and deeper public debate – a combination of the wisdom and eloquence that Cicero argued so forcefully for?