Will an incoming government boost Australia's climate aid?

‘How will your party deliver on the Paris Agreement on climate change?’ This was one of ten questions that the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID) asked of parties contending this year’s election to gauge their positions on aid.

It’s a fair question to ask. Climate change poses major risks not only for Australia but particularly for less wealthy countries in our region. While aid rarely features prominently in Australian election campaigns, climate change has again become an election issue as the domestic impacts of warmer temperatures accumulate, from unprecedented bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef to bushfires in Tasmania.

And only half a year ago Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was in Paris to lend support to a landmark UN climate deal. At the Paris summit wealthy countries reaffirmed [pdf, para 54] their collective pledge to mobilise US$100 billion in climate finance by 2020, and agreed to set a new longer-term target starting with that figure as a floor.

What do the parties say?

Four parties answered ACFID’s survey. The responses on climate change range from the unsurprising to the uninformative to the unenlightened.

Let’s start with the unenlightened:

Family First believes that affordable energy is necessary for poverty alleviation; that increased CO2 is improving crop yields and so reducing hunger; and that technological advances are increasing the competitiveness of renewables so the industry could compete without government subsidies.

The clear implication here is that climate change is not a problem, that it’s actually good for development, so it would be a waste of aid to fund any action at all. While the need to tackle energy poverty is widely recognised, it doesn’t follow that the answer is to keep pumping out pollution that will do more to exacerbate poverty in the long term than alleviate it. It is also fairly well established that the negative impacts of climate change on crop productivity will far outweigh any positive influence of increased carbon dioxide on crop fertilisation.

Moving onto the uninformative: both Labor and the Greens’ responses are silent on international funding. To be fair, ACFID’s question didn’t refer specifically to climate-related aid, but it was hardly a trick question — after all, it was a survey on aid. Both parties do little more than reiterate their targets for reducing domestic emissions. Labor adds that it has a Climate Change Action Plan [pdf], but the plan says nothing about support for other countries. While Labor’s Foreign Policy states that ‘climate change is an existential threat to some of our neighbours in the Pacific’ and includes vague references to supporting adaptation in vulnerable countries, there are no concrete commitments to be found.

While the Greens’ response doesn’t cross-reference their policies, we can find a bit more substance elsewhere. The last principle of their climate change and energy policy covers international assistance, and their policy on aid and development [pdf] includes calls to ensure that climate change funding is not redirected from existing aid initiatives, and to target support towards adaptation, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region.

Finally, the unsurprising: the Liberal Party says that ‘it would commit $1 billion over five years to help developing countries build climate resilience and reduce emissions’. We may quibble with the grammar here. The government has already committed at least $1 billion over five years — the Prime Minister did so in Paris — so it’s just a question of whether a new government would stand by that commitment. Still, to their credit, the Liberals were the only party to mention a concrete figure for climate finance. Whether that figure is credible is another issue we return to shortly.

What can the parties’ track records tell us?

To work out what either of the major parties may do if they win the election (leaving aside for now the prospects of a minority government), one possible guide is evidence from past practice. Here we draw on a new research paper we’ve written that looks at the politics of climate finance in Australia over the past decade.

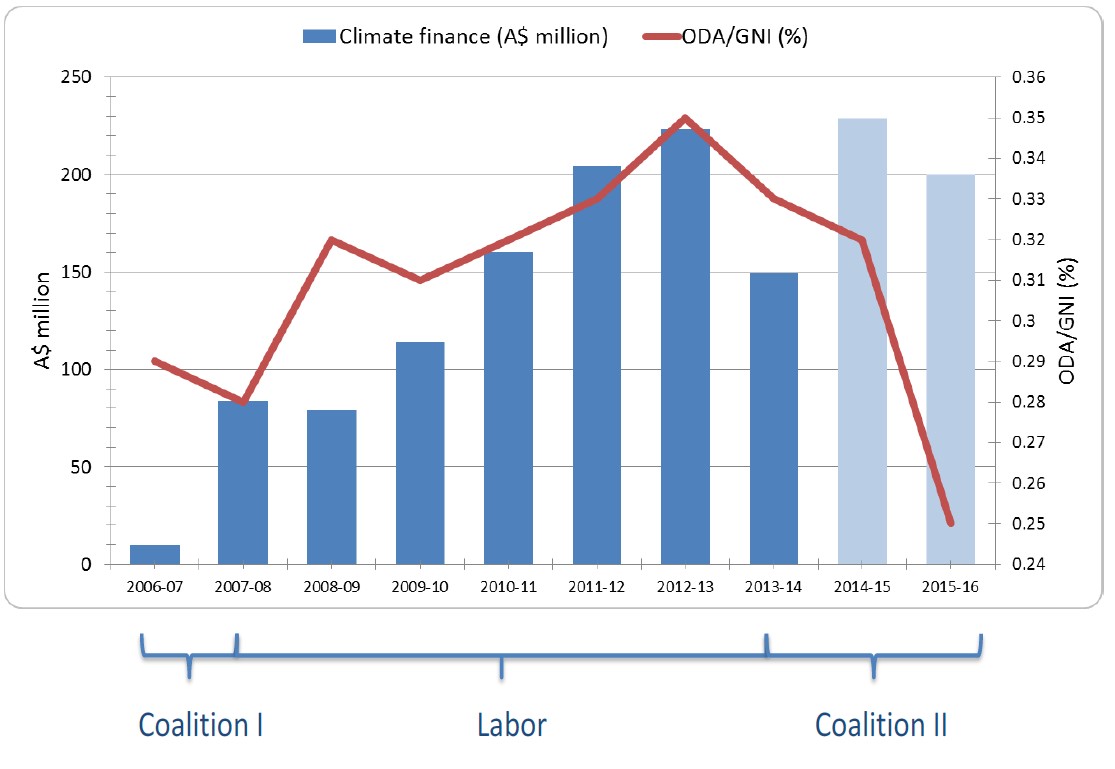

Some broad trends are evident. By and large, Labor governments have been more supportive of strong action on climate change and more aid than Coalition governments.

But if we look beyond these broad trends to their track records on climate finance, the contrast is not quite as straightforward. For all of the Coalition’s reluctance to act on climate change during Tony Abbott’s prime ministership, the government did stump up A$200 million for the Green Climate Fund in 2014. And even before Turnbull had become Prime Minister, Australia’s climate finance was higher than it had been under any Labor government. While Labor’s funding peaked at A$223 million, in 2014-15 it reached A$229 million.

Source: Pickering and Mitchell (2016), Figure 1

Again, when comparing these two peaks there’s more than meets the eye. Figures for 2013-14 onwards are based on a different accounting methodology [pdf] that may take a more expansive view of what counts as climate-related aid than previously. That doesn’t mean the new methodology is suspect — it just makes it harder to compare funding over different time periods.

A different way of comparing each government’s track record is to look at how their share of total climate finance provided by wealthy countries has changed over time. Australia’s ‘fast-start’ climate finance pledge (2010-11 to 2012-13) launched under the Rudd Labor government was around 1.9 per cent of all funding pledged. The Abbott government’s pledge to the Green Climate Fund likewise came in at 1.9 per cent of the total.

But Turnbull’s announcement at Paris saw Australia’s share drop to around 0.8 per cent of total estimated annual funding for 2020. Whereas some contributors (including Germany and the European Commission) doubled their existing levels of climate finance, Australia pledged only to maintain funding at least at 2010 levels (around A$200 million a year). So while the nominal value of Australia’s climate finance remains steady, its real value and its share of the total are falling.

By contrast, ACFID’s election platform [pdf] calls for Australia to boost its annual public climate funding to at least A$558 million immediately. And Oxfam [pdf, p.11] has called for Australia to boost public funding to A$1.6 billion by 2020 (based on Australia’s share being around 2.4 per cent of the total, as estimated in a previous ANU working paper).

What can we expect after the election?

Would a Labor government boost Australia’s climate finance? As we discuss in our paper, the previous Labor government was more determined than the present government to pull its weight in international climate negotiations. Labor has also announced that it would reverse some (if not all) of the Coalition’s cuts to aid. So it’s possible (although by no means certain in the absence of specific election promises) that a Labor government would revisit Australia’s Paris pledge.

If the Coalition remains in office, is anything likely to change? If re-elected, Prime Minister Turnbull may have more sway over the climate change naysayers in the Coalition than he has now. Even so, the government may not be inclined to formally revisit its freshly minted Paris pledge any time soon.

Still, a government of either political persuasion could make use of the upwards flexibility in the wording of the Paris pledge: that is, to contribute ‘at least’ A$1 billion over five years. A much-needed strategic review of the government’s climate finance priorities could provide an opportunity to map out a more ambitious program.

Based on the experience of the past decade, Australia is likely to remain under international pressure to pull its weight. Not only are we co-chairing the Green Climate Fund board again this year, but the Fund’s replenishment process is likely to kick off in the next year or so [pdf, p.29]. When that happens, Australia’s role will be in the spotlight again.

Governments don’t always respond to peer pressure, but the example of the Abbott government’s reversal on the Green Climate Fund shows that under some circumstances countries will change tack to avoid international isolation.

With climate change impacts only set to increase over time, pressure will continue to rise for wealthy countries to pull their weight in mobilising finance to support poorer countries’ transition to clean energy and investments in adaptation. Wealthy countries will also need to look to forms of support beyond aid, which may include migration arrangements for climate-displaced populations.

For whichever party wins government on 2 July, questions raised by ACFID and other voices in public debate should be a pertinent reminder that the issue of climate change is not going away, and that Australia has a constructive role to play in ensuring unavoidable impacts do not destabilize our region.

This article was first posted on Devpolicy.org.