Governance (is) for the birds.

The International Waterbird Census, one of the longest running citizen-science exercises in the world, reached 50 years of operation in January. Every year in January and February enthusiastic birders record the numbers of waterbirds across several thousand sites in 143 countries, with between 30 and 40 million waterbirds counted each year. Co-ordinated by the NGO Wetlands International (descendant of the International Waterfowl Research Bureau, founded in 1954 and originator of the Census) the results signal any decreases, increases or fluctuations in waterbird populations. Knowledge of those changes helps direct conservation and management action on wetlands critical for the species survival.

On World Wetlands Day – February 2 –the slightly younger Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention) turned 45. World Wetlands Day had the theme of Wetlands for our future. Yet many other emblematic and enigmatic species rely on wetlands as well. The world’s migratory shorebirds are certainly in that category, and they are the focus of the Census. Data from the early counts reinforced the need for a convention to conserve and mange wetlands, resulting in the birth of the Ramsar Convention in 1971. It took a further four years for the Convention to come into force but Australia can be rightly proud of being the first signatory on the Convention’s roll. A direct result of the census has been the identification of almost 1 million km2 of internationally important wetlands listed under the Ramsar Convention.

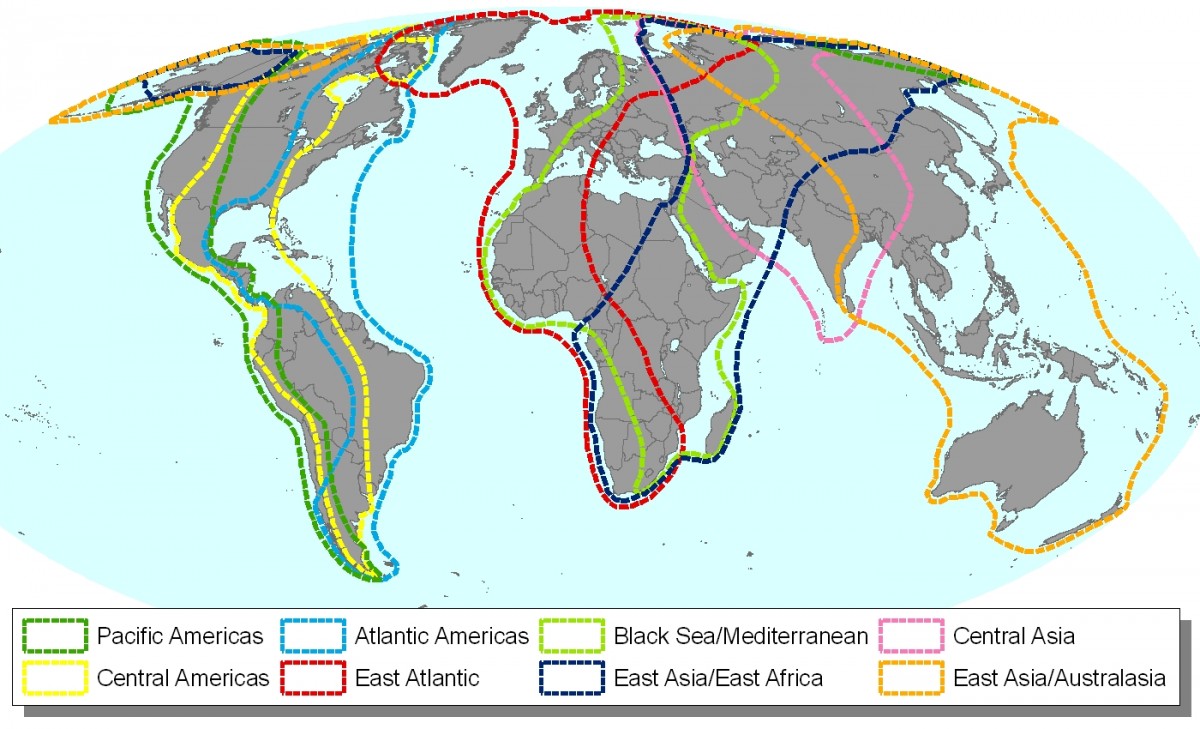

Being a global exercise, the census is important as many waterbirds spend their lives in several countries during any one year, feeding and breeding in different hemispheres. So their survival relies on a series of available wetlands along the routes they travel, known as flyways. The map shows the major global flyways. Information from the census contributes to regular assessments of nearly 900 waterbird species, many of which are increasingly threatened by habitat changes. In many countries the census serves as the sole national waterbird monitoring scheme. It has helped identify and monitor recovery of species in decline or threatened, as well as those that have increasing populations. Globally, 40% of waterbirds are in decline, 40 % stable and 20% increasing. Of those in decline in our neck of the woods, most are far-ranging migrants, travelling from Australia north through Asia to far-north china, Mongolia and far-eastern Russia. Species that roam around Australia or migrate to just the near north are usually static, fluctuating or increasing.

Successive Australian governments, from the mid 1970’s onwards, have sought international co-operation on migratory bird conservation. Bilateral Migratory Bird agreements with Japan and China, and much more recently with South Korea, are in place. These agreements helped focus attention on the need for wetlands to be available for shorebirds migrating from Australia northwards in the flyway connecting Australia north to north-east China and Siberia. But while bi-lateral agreements are useful, full international action remains key, especially through the Ramsar Convention and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). Of course, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) also has competence over migratory species (Article 7) as well as programmes on inland water and coastal and marine biodiversity. But the range of countries signatory to these conventions ranges widely. Furthermore, the focus also varies from conservation of the species (CMS) to conservation of the habitat (Ramsar), or both (CBD). As some countries in the Asia-Pacific region are not included in those Conventions, Australia initiated discussions in the 1990’s to develop an agreement involving all countries covering the East Asian - Australasian flyway. The result was the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Partnership, which also celebrates an important birthday in 2016, being 10 years old in November.

Other flyways have agreements or arrangements in place. launched in 1986 the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network for the Americas – WHSRN - covers the three flyways of the Americas. The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds, a regional agreement under the CMS signed in 1999, covers the East Atlantic and Black Sea -Mediterranean flyways. Although the flyway world is broadly covered by these three arrangements, there are obvious gaps – especially in the central Asian and the East Asia – East Africa flyways. The Siberian end of this latter flyway overlaps with the East Asia – Australasian flyway and species from southern Africa and Australia meet in the insect-rich Siberian summers.

The different focus and governance status of these different flyway arrangements, and very loose link with the Ramsar Convention provides an imperfect solution for the growing crisis in waterbird conservation. As the WHSRN website says, “scientists and volunteers (are) scrambling to understand the natural and human induced perils these intrepid migrants encounter in hopes of stemming their decline. For some species, it is a race against time”. The race to conserve these species is important because, while special in themselves, they also link far distant ecosystems and affect thus the services they deliver.

In terms of better governance clearer and shared priorities between conventions and agreements is vital. Co-ordinating the timings of meeting of the scientific and governing bodies is also critical. The CBD could play a role here, but it has a groaning agenda, and has tended to become severely bureaucratic in recent years. There is a case thus for an over-arching liaison group meeting at least annually to coordinate research effort, and focus management priorities across the range of agreements. While this is clearly a government responsibility there is a case for tasking Wetlands International to drive this liaison effort, perhaps in tandem with UNEP. In that way governments can live up to their agreed commitments, but in a more joined-up way.

Such a suggestion would not be universally welcomed, but there is an urgent need to cut through the burgeoned bureaucracy to deliver results shown to be necessary by the continued counting of citizen scientists. With more effective governance structures the census results will continue to secure a future for these classic animal FIFOs.