Social Media and Political Campaigning: A Look at the 2015 UK General Election Campaign

The widespread adoption of digital media represents a “second media age,” contrasted with the first media age of broadcast media (Poster 1995). Each era of communications is not temporally bounded and totalizing as aspects of each media era persist in political campaigning: we still have direct mail campaigns, door knocking, both human and automated telephoning, books, large volumes of TV, radio and print advertising, and of course stump speeches. However, the prevailing means of communication in any era has significant consequences for political organization. Organization is fundamentally a communication process and as new communication technologies with unique communication affordances are adopted in a field of activity, it is entirely possible, if not probable, this has consequences for campaign organization carried out through these media.

In terms of new communications capacities, perhaps one of the more innovative uses of social media platforms is the ability to directly respond to others. In a broadcast era of politics, campaigns were predominantly known to supporters through their mediated representations. Broadcast media outlets involve a series of intermediaries whereby journalists select what to cover and how to characterize and contextualize it. In addition to journalists, news broadcasters as organizations and the systems in which they operate structure what aspects of campaigns and the flow of communications covered and the manner in which it is covered. The mediating role served by news organizations means that interactions between campaigns and other entities – allied campaigns, opposing campaigns, organized interests, media entities, laypersons and so forth – are indirect and depend on an alignment between the interests of journalists, media organizations, and the the campaigns. Under such conditions, broadcast media make for better monological communications, crafted in accordance with media logics (e.g. short attention-grabbing sound bites).

These communications become subject to both the terms of media reporting as well as its temporal rhythms. This makes the process of campaigns responding to others through the media a highly probabilistic and extended process, undermining the ability to use the medium to carry out dialogical interactions. In this regard, Twitter affords unique capacities for political campaigns to engage in direct, two-way communications. While this capacity is transformative in terms of the range of communication operations available to political campaigns, whether or not it is transformative in terms of achieving campaign functions and goals is another matter.

Twitter and the 2015 UK General Elections

Twitter communications have become increasingly ubiquitous within political campaigns. Many popular news outlets dubbed the 2015 UK General election a “Twitter election” (here, here, and here). This reporting highlights the extent to which campaigns tweeted and were tweeted about. However what would it mean for the election to be a Twitter election? Certainly 2015 saw a substantial rise in the level of tweeting by campaigns. In 2010, the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, and Labour parties and their leaders produced a combined 1043 tweets during the UK general election campaign (Jensen and Anstead 2014). In 2015, the Liberal Democrats alone tweeted 5,711 times during a 37 day campaign window (the Conservatives produced 3,349 tweets and the Labour party, 2,175, in addition to tweets produced by each of their party leaders). Both the Obama and Romney campaigns placed a great deal of emphasis on their tweeting during the 2012, the latter relying on a team of staff to carefully scrutinize each tweet produced and the former using the medium to make timely interventions in the ongoing flow of campaign contestation (Kreiss 2014). Evidently, campaigns treat tweeting as if it serves important functions and they are willing to devote resources to tweet effectively. What those campaign functions are, are however less well understood.

Twitter affords campaigns the ability to communicatively intervene by sending a direct communication which is subject to responses from others, retweeting or forwarding on a message created by others, or responding directly to others. He capacity to respond to others who need not be part of one's network of friends is a unique aspect of Twitter that differentiates it from other social media platforms like Facebook where communications are more organized around pages administered by campaigns and the posts responses of those who follow the campaign. To understand how Twitter is used by campaigns, a first step (and the one taken in this blog post), is to understand who campaigns respond to.

Between 31 March 2015 when the British parliament formally dissolved until the morning of election day, 7 May 2015, the campaign accounts of the eight leading parties and their leaders (except for the British National Party which had an interim leader who did not use Twitter), produced 22,397 tweets. Of those, there were 2,032 replies. These ranged from David Cameron's zero replies to the Liberal Democrats 951 replies. Natalie Bennett of the Green Party 468 replies which accounted for 38.17% of all her tweets posted during the campaign and Ed Miliband had 40 replies to tweets, though 37 of those were to himself as a means sending an extended message exceeding 140 characters. The remaining three replies were to Abby Tomlinson, a young Labour supporter who developed the meme of Ed Miliband as a political sex symbol.

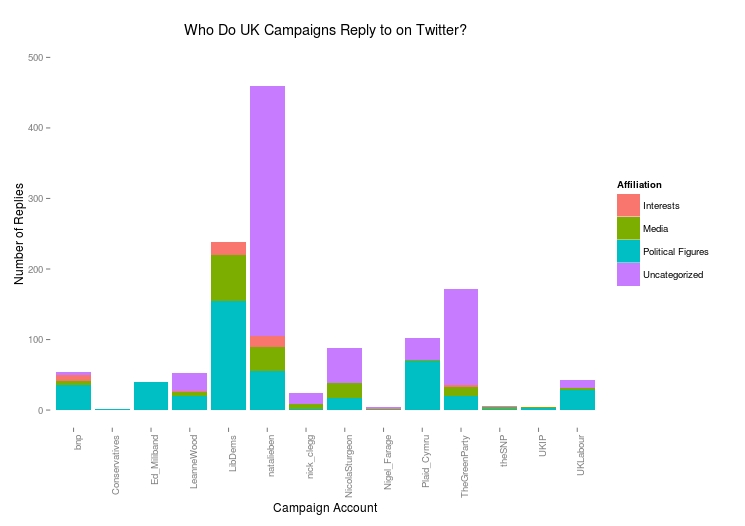

We can get an idea of who is replied to by extracting their Twitter IDs from the tweets and looking them up through the Twitter application programming interface (API). Each Twitter profile has a space where a brief biography can be listed. We can divide those between accounts which are likely tweeting in an official capacity (candidates, political parties, interest groups, journalists and media organizations) from laypersons who are not programmed in some way to participate in the shaping of political life. Given the centrality of the party to campaigns in the UK, the various candidates for office as well as the organizational accounts affiliated with various offices and functions within parties typically mention those party affiliations in the account biography. Accounts run by interest groups or those holding a position within an interest group and journalists and media organizations likewise typically list that affiliation as a matter of marketing the brand. Coding these biography lines in the Twitter profiles enables us to identify who various campaigns reply to and whether they reply to accounts operating in an official or professional capacity or accounts from laypersons otherwise unaffiliated with a campaign. Many of these profiles could not be retrieved due to changes in the screen names or the closure of accounts. The proportion of political figures and party-affiliated accounts, journalists (including bloggers), and interest groups as well as those which do not fall into any of these categories are presented in the below figure. The Green party and their leader have the largest potion of replies which are not directed at accounts which typically participate in the campaign in a professional capacity. Over half of Nicola Sturgeon's replies were otherwise not classified in any of these three categories.

There is some replying to media officials but for the most part, these accounts are replying to other campaigns, apart from the Green party and its leader as well as Nicola Sturgeon's account. This is uniquely a space afforded through Twitter where campaigns can directly reply to other campaigns or their activists. These data do not distinguish between those accounts aligned with a campaign (e.g. UKLabour replying to Ed Miliband) and those replying to other campaigns. Replying to an allied campaign however is not without risks as it may be seen as undercutting the statement replied to. Rather it seems more likely that these replies are to activists and opposing campaign. This finding would be consistent with other research indicating that the majority of those tweeting about political campaigns are highly partisan to begin with (Bekafigo and McBride 2013).

Apart from the Greens and to a limited extent the SNP leader, Twitter does not appear to be a space of political conversion. Rather it involves preaching to the choir by replying to activists or other campaigns. It represents a continuation of the prosecution of the campaign. Labour and Conservative avoidance of replying to unaffiliated persons perhaps suggests they feel they do not need to reach out beyond their base and it is merely a matter of mobilizing supporters (Hersh 2015). The fact that the Greens are a small party does not help explain why they reach out to those who are not party officials, organized interests, or media officials as the BNP and UKIP both are small national parties and they do not reply to others on Twitter. Social media may serve then serve different functions for parties but it remains to be seen what helps explain that as size and ideology in this case do not.

References:

- Bekafigo, Marija Anna, and Allan McBride. 2013. “Who Tweets About Politics? Political Participation of Twitter Users During the 2011Gubernatorial Elections.” Social Science Computer Review: 0894439313490405.

- Hersh, Eitan D. 2015. Hacking the Electorate: How Campaigns Perceive Voters. Cambridge University Press.

- Jensen, Michael J., and Nick Anstead. 2014. “Campaigns and Social Media Communications: A Look at Digital Campaigning in the 2010 U.K. General Election.” In The Internet and Democracy in Global Perspective, Studies in Public Choice, eds. Bernard Grofman, Alexander H. Trechsel, and Mark Franklin. Springer International Publishing, p. 57–81.

- Kreiss, Daniel. 2014. “Seizing the moment: The presidential campaigns’ use of Twitter during the 2012 electoral cycle.” New Media & Society: 1–18.

- Poster, Mark. 1995. The Second Media Age. Cambridge: Polity.