"Why Should I Go to School if You Won't Listen to the Educated" - why letting ignorance trump knowledge is a big problem for democracy.

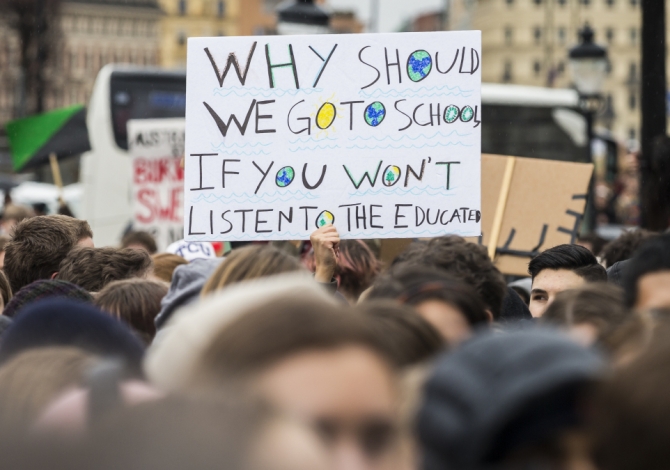

Perhaps the most telling of the thousands of global climate strike placards around the world last week were the one reading ‘why should I to school if you won’t listen to the educated’?

Privileging ignorance over knowledge, rash opinion over reasoned debate, and sectional self-interest over the common good are signs of democratic failure. This means that in liberal democracies like Australia, climate strikes were as much about a political system not working as it should, as they were about the details of environment policy.

The climate strikes raise important questions about how the political system makes decisions; especially how and why the relationships between fact and opinion work. The parliamentary family law inquiry that the Government announced last month raises the same questions. It follows an independent expert inquiry by the Australian Law Reform Commission earlier this year and the government hasn’t yet responded to its 60 recommendations. The parliamentary inquiry has already been compromised by misinformation spread by its expected deputy Chair, Pauline Hanson, and the problem of prejudice often having more sway than evidence of what works in indigenous policy is well established.

How, then, do we create a democratic culture where voters expect to think about hard policy issues, ask hard questions of parliamentary candidates, and demand serious, informed and well thought out responses? How do we create a political culture that ensures that serious political parties have the insensitive to pre-select only candidates who are up to the task in this respect?

Public confidence in the political system is low. Voters do not think well of Members of Parliament. Even though these are people who work long hours, spend extensive periods of time away from home and are subject to constant public scrutiny.

However, democracy belongs to the voters. At least theoretically, nobody sits in the House of Representatives without significant public support. No sitting member is re-elected unless their constituents think they’ve done a good job. So perhaps it’s the voters who are not doing a good job - expecting a great deal, but not having the capacity or the will to elect people to parliament who can meet those expectations?

On the other hand, casting an informed vote is difficult. Knowing the individuals whom one’s vote will elect to the Senate is almost impossible. The Senate is, by design, the ‘unrepresentative swill’ that Paul Keating called it in 1989.

The politicisation of the public service, and the anti-intellectual values that this creates, means that voters can’t be sure that the broad philosophical ideas that candidates promote at election time will be developed into robust, informed and workable public policy through the ‘free, frank and fearless advice’ of politically neutral policy experts.

The fact that the news media doesn’t always see its job as providing a politically neutral well-informed service to the public, but a platform for opinion, also makes it hard for the ordinary voter to develop the knowledge to contribute usefully to public affairs.

If the placard waver is right to suggest that listening to the educated is a good thing, it is the educated voter who must create the expectation that the expert is heard. The climate strike reflected that expectation. But taking it further requires significant democratic reforms.

Both Houses of Parliament ought to be elected according to voting methods that are mathematically simple enough for each voter to know exactly which individual they are electing to parliament. In this way, voters may scrutinise the values and priorities of candidates and be sure that they are voting for a candidate whose ideas and aspirations are similar to their own.

The Senate’s ‘above the line’ voting system, where voters choose a party and, effectively, the party chooses the individuals who sit in the upper House removes the voters’ responsibility. It removes the capacity to make a choice and accept personal responsibility for that choice. For as long as it is constituted from party lists, the Senate cannot fulfil its function as a House of review. Its members are not independent reviewers but people whose loyalty is to the party; making the Senate a House of patronage. The contribution it should make to informed public debate by holding the government to account can’t occur.

Regulatory reform to the news media is also a matter of democratic urgency. The criticisms levelled at the Conversation for the decision that its pages would not be a vehicle for the spreading of misinformation on climate change policy showed the depth of that urgency. The idea that a news outlet should openly promote ignorance over fact, or accept misinformation as just a difference of opinion, sets aside the news media’s essential democratic function.

Differences of opinion are important. People come to politics with different values and interpretations of what is good and of what are the purposes of public policy. Mediating those differences is the purpose of democratic government. However, the voter whose duty it is to cast an informed vote, must be sure that it will be exposed when some policy ideas are not grounded in fact. There is a case for regulation to keep lobbying and journalism easily identifiable and separate parts of the political process.

Objective news media plays an important educative role. However, there is also a case for education for citizenship being a more explicit function of the education system. This means understanding the technical workings of the institutions of democracy, but also having the critical reasoning skills and commitment to the common good that a functioning democracy presumes.

Being a citizen means being informed. But there is much about the ways that Australian democracy works that makes being informed an unnecessarily difficult task.

Image: Michael Campanella / Getty Images