Reshaping the Politics of Contemporary Democracies: Cosmopolitan versus Shrinking Dynamics

In a recent pamphlet, Jeremy Cliffe argues that 21st Century politics will be shaped by the emergence of a cosmopolitan shift in demography. This phenomenon is led by the big cities that are attracting ever-more people, jobs and investment for their university-educated and ethnically diverse populations. We would argue that the advance of cosmopolitanism tells only half the story and that the dilemma for political parties is acute as Britain’s future lies on two divergent paths: one cosmopolitan and one shrinking. To add further complexity to this predicament, citizens in both types of area share a lack of faith in politics.

There is growing divide between global cosmopolitan cities and shrinking urban conurbations with the dynamic of global competition driving both developments. Cosmopolitan centres are the gainers in a new system of global production, manufacturing, distribution and consumption that has led to new urban forms made possible by the revolution in logistics and new technologies. These global urban centres are highly connected, highly innovative, well-networked, attracting skilled populations, often supported by inward migration, and display the qualities of cosmopolitan urbanism. Simultaneously, other towns, cities and entire regions are experiencing the outflow of capital and human resources, and are suffering from a lack of entrepreneurship, low levels of innovation, cultural nostalgia and disconnectedness from the values of the metropolitan elite, and are largely ignored by policy-makers. These shrinking urban locations are the other side of the coin; for them the story is of being left behind as old industries die or as old roles become obsolete, and as successive governments have left them to fend for themselves. Populations may be declining, the skilled workers and the young are leaving in search of opportunity and these places are increasingly disconnected from the dynamic sectors of the economy, as well as the social liberalism of hyper-modern global cities in which the political, economic and media classes plough their furrow.

These developments are not temporary or transitional. Globally connected urban areas are experiencing a sustained and self-reinforcing growth and shrinking cities are struggling to overcome the challenges of decline as part of a new capitalist order. The shrinking cities as new urban analysis suggests cannot easily be dragged into the slipstream of cosmopolitans by policy interventions. The forces that are driving rampant cosmopolitanism are also driving the gradual withering of shrinking conurbations.

What is also clear is that these trends are reshaping and fracturing politics in such a way that creates a major dilemma for all parties in the short- and longer-term: political attitudes and engagement are heading in opposed directions in the two types of area. A survey by Populus, commissioned by the Universities of Canberra and Southampton allows us to compare cosmopolitan areas to shrinking areas to explore these different forces. Using Mosaic geodemographic categories, the survey identified the fifty constituencies most closely resembling the profiles of Clacton and Cambridge respectively – places that previously have been characterised as harbingers of Britain’s very different futures. This approach allows us to explore differences in political attitudes and participation in cosmopolitan and shrinking settings. To illustrate these distinctive demographics of place, some 45% of respondents in cosmopolitan areas appear to have post-degree education (i.e. left full-time education at 24+) compared to 20% of those in shrinking areas. In shrinking locations, 32% of respondents consume tabloid newspapers or websites, whereas in cosmopolitan areas the figure is only 19%. But more importantly what are the differences in terms of political outlook and forms of politics that are being practiced?

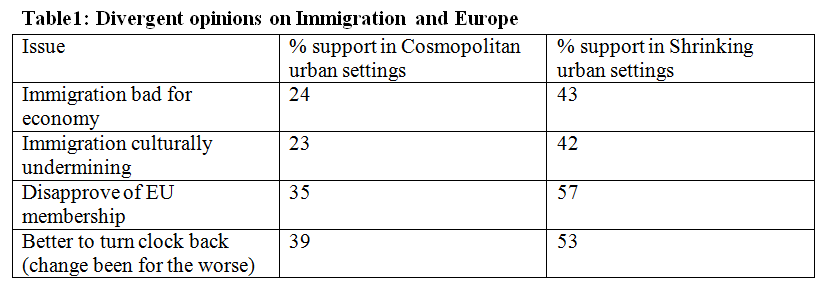

These communities have very different attitudes on issues of Europe and immigration, as well as more broad views about social change, as Table 1 shows. Shrinking areas tend to be more negative about recent developments, expressing concern about both immigration and the EU. In this respect, cosmopolitans have a much more outward-looking perspective on forces and institutions of the global economy, whereas shrinkers are more resistant.

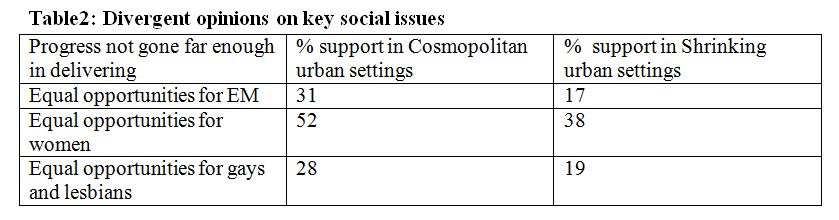

The populations of these places exhibit distinct views on important areas on social change, as shown in Table 2. Cosmopolitan areas tend to display much stronger support for more to be done to create equality across a range of social divides – ethnicity, gender and sexuality. This in part reflects the contrasting social contexts of these two sets of places, but also hints at the sorts of politics that they might produce.

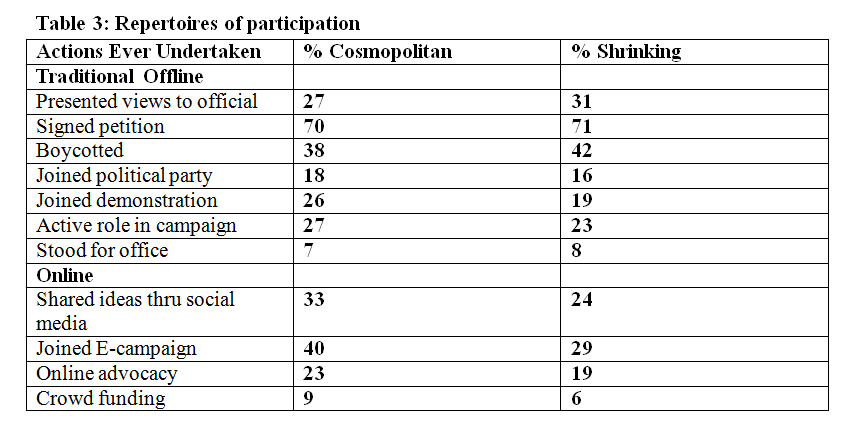

More significantly, citizens in cosmopolitan and shrinking areas engage in politics in distinctive ways, as Table 3 demonstrates. There are strong similarities for participation in a range of traditional off-line methods, but some differences in political activity that takes place on-line. This suggests that the cosmopolitan/shrinking schism may be another venue for the digital divide.

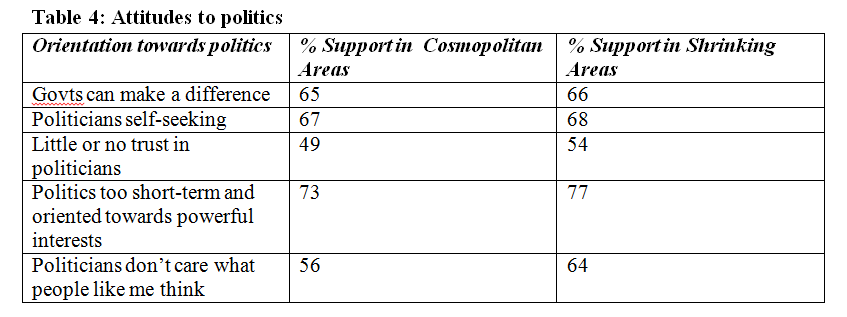

Citizens in cosmopolitan and shrinking places tend to hold contrasting views about trends of social change and are developing their own repertoires of engagement. Despite this, both sets of citizens are very doubtful about the politics that is currently on offer. As Table 4 indicates, both share a lot of the same disaffection towards politics and politicians. Both groups think governments can make a difference but fear that politicians are too self-serving and short-termist. Both have little trust in politicians and feel that politicians don't care about them, although that view is more strongly held marginally in shrinking areas.

Citizens in cosmopolitan and shrinking places tend to hold contrasting views about trends of social change and are developing their own repertoires of engagement. Despite this, both sets of citizens are very doubtful about the politics that is currently on offer. As Table 4 indicates, both share a lot of the same disaffection towards politics and politicians. Both groups think governments can make a difference but fear that politicians are too self-serving and short-termist. Both have little trust in politicians and feel that politicians don't care about them, although that view is more strongly held marginally in shrinking areas.

What does this all mean for the future of politics. Given this diversity a centralised nationally oriented party structure – on both left and right – is going to increasingly struggle to cope with this divergent world. The challenges include: that recruitment and candidate selection becomes more complex and needs to be locally sensitive. Social media engagement might have more of a grip in cosmopolitan rather than shrinking locations so it is unlikely to become a universal tool in the immediate future. Above all it is difficult to present the same face to shrinking and cosmopolitan populations; and it is far from clear how any party can bridge that divide of economic change and social outlook that will only increase in intensity as their experiences diverge and become locked in a self-reinforcing cycle of economic growth or stagnation and civic culture.

What does this all mean for the future of politics. Given this diversity a centralised nationally oriented party structure – on both left and right – is going to increasingly struggle to cope with this divergent world. The challenges include: that recruitment and candidate selection becomes more complex and needs to be locally sensitive. Social media engagement might have more of a grip in cosmopolitan rather than shrinking locations so it is unlikely to become a universal tool in the immediate future. Above all it is difficult to present the same face to shrinking and cosmopolitan populations; and it is far from clear how any party can bridge that divide of economic change and social outlook that will only increase in intensity as their experiences diverge and become locked in a self-reinforcing cycle of economic growth or stagnation and civic culture.