Post-Democracy: Does Populism have a Place in Britain?

For democracy to be flourishing, movements emerging from the population must, from time to time, be able to give the system a shock, writes Colin Crouch. Yet that raises questions about xenophobic populism: can it ever be a form of democratic irruption against the complacency of liberal post‐democracy?

British democracy reached an ugly moment on 3 November 2016, when the Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph devoted their front pages to the three judges of the Supreme Court, with respective headlines reading ‘Enemies of the people’ and ‘The judges vs the people’. The judges’ ‘offence’ had been to rule that Parliament had a right to have certain votes on the process of the United Kingdom leaving the European Union. In subsequent days some government ministers echoed the phrases, until the Home Secretary, under pressure from judges, issued a statement stressing the importance of the rule of law. However, the government itself continued in the same spirit when it attempted later to revoke EU legislation without bringing it to Parliament. The people had spoken; government would interpret their will. Parliament was a potential enemy of that will.

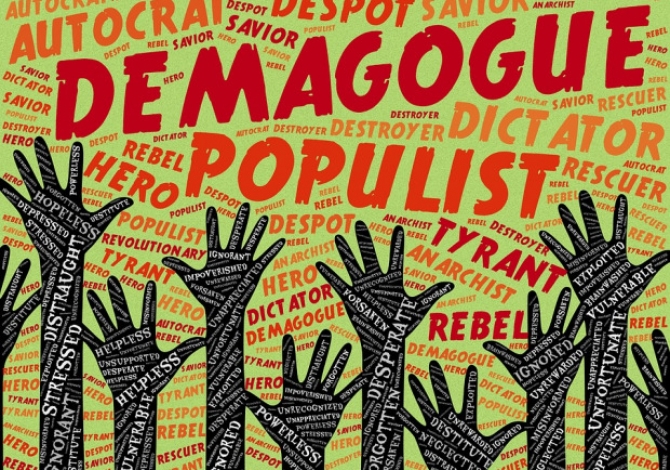

This was a confrontation between two concepts of democracy: does it (as in liberal democracy) denote a set of institutions that include expressions of popular will, but which surround them with others that ensure elaboration of that will, guarantee continued debate so that democracy can function again at a future date, and even limit the powers of those who claim the right to exercise the popular will? Or is it (as is increasingly happening in once-stable democracies) the direct, unmediated voice of a people expressed on a particular day and then interpreted for them by leaders who have no further recourse to them: a populist democracy?

Shocks to the system

I’ve previously argued in my book Post‐Democracy that for democracy to be flourishing, movements emerging from the population at large must, from time to time, be able to give the system a shock. They raise new questions that the elite would sooner not discuss.

In recent years, the three movements that have been doing this are feminism, environmentalism, and xenophobic populism. Xenophobic populism has become by far the most dominant. And if democracy expresses itself in disruptive challenges emerging from the citizenry and challenging the complacency of elites, I have to welcome the initial appearance of these various movements as refreshments for democracy. But should one welcome the continued presence of xenophobic populism as a democratic irruption against the complacency of liberal post‐democracy, and if not, why not?

Xenophobic populism as a problem

Brexit, for example, bears many of the hallmarks of xenophobic populism. Its campaign was targeted against internal (immigrant) and external (EU) foreigners. It was a plebiscite with decidedly anti‐parliamentary overtones. The defeated minority, although large (48%) was expected to surrender the usual democratic right to continue debating.

The rhetorical attack on claims that Parliament should submit the process to scrutiny is pure populism. Equally, so is the doctrine that any right to vote on the issue again would be hostile to the people’s will. The initial irruption of populism like this within a society may well invigorate its democracy, bringing neglected issues to the table and putting established parties and elites on their mettle. It is difficult for those with no seat at the political table to acquire one without invading spaces occupied by present incumbents. However, unless such movements rapidly change their character to accept restraining institutions, their continued presence can threaten democracy.

Democracy requires the protection of the people from potential manipulation by their leaders. It endangers itself if it is deemed to justify political control over the law and other intermediary bodies. Also, there must always be another election. Opposition and government parties alike must have the right to go on debating.

Today’s minority may become tomorrow’s majority, which also means that majorities must beware how they treat minorities, as that may be their position in a few years’ time. This expectation of a changing balance of power is the best safeguard we have that those currently with power will not abuse it. The tendency of populist movements to regard themselves as the perfect and final manifestation of democracy renders them as its enemies.

Rude invaders

But the deficiencies in democratic institutions revealed by the rise of populism remain. It is essential that rallying calls to oppose populism do not lapse into defences of corruption, of the plutocratic capture of government, of party systems that do not represent society’s most important divisions. Rude invaders must be welcome, provided they accept that they themselves must become subject to constraints that safeguard democracy’s future.

In post‐industrial, post‐religious, post‐modern societies, are we just a mass of loosely attached individuals blown around by confusing blasts? The political right has produced an answer to that question: its determined rootedness in nation, though many moderate conservatives and liberals will be in despair at this. Do the left and centre have anything of similar strength to offer, roots in deeply felt social identities? Cosmopolitan liberalism by itself risks failing to have the courage of its lack of convictions. Debate on the left and centre must now turn to this search.

The future is female

One possibility is that, just as the original labour movement was essentially a male phenomenon that interpreted the problems of all working people through the eyes of ‘breadwinner’ men, in post‐industrial society, many of the problems of such people may be best articulated by women. They experience more keenly issues of work-life balance, of precariousness in the labour market, of deficiencies of care services, of the manipulation of consumers, though these are problems that men share too. Many work in the public and care services that embody the main challenges to both neoliberal and intolerant world views.

This does not imply the formation of separatist women’s parties – the hope is that women will become the spokespeople of many men too. It does require a strong civil society surrounding formal politics with other forms of representation, including organisations that express women’s continuing experience of various kinds of exclusion and the development of political agendas to counter them.

There is perhaps a further element. Much about rightist populism is very macho: from the male swaggering of leaders like Putin and Trump to the violent fringe that attaches to most xenophobic movements. The very recent widespread resurgence of feminism could be reaction against that ugly face of masculine politics.

Note: the above is adapted from a chapter in Rethinking Democracy, edited by Andrew Gamble and Tony Wright (Political Quarterly Monograph Series, 2019).

This blog was first published by the British Politics and Policy blog at the LSE