NATSEM BUDGET 2016: towards digital-era governance?

‘Things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then happen faster than you thought they could’. Larry Summers

The key stories underpinning Budget 2016 are likely to oscillate between narratives on whether the budget will ‘repair’ the economy, help Australia to avoid ‘recession’, ‘renew’ the economy or whether it is ‘fair’. There is, however, a budget story that is less likely to attract media attention as it will not conspicuously impact immediately on the dollar in every Australians pocket. The ramifications, however, will have a dramatic effect on the relationship between government and citizen. The Australian Public Service (APS) is currently undergoing a historic shift towards the establishment of Digital Era Governance (DEG) and budget measures are likely to further precipitate change. This constitutes more than an increased uptake in IT solutions – it challenges the established ways in which policy is made and public services are delivered, monitored and evaluated. Most significantly, it questions dominant public sector cultures and values. We now live in a digital era, where rapid and disruptive change in societal behaviour and industrial and economic patterns have become the norm and government is finally waking up to the realities of the new economy. As the Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull stated in his April 20 address to the Australian Public Service in the Great Hall at Old Parliament House:

“Digital disruption, greater transparency in data and information, contestability of advice, rising community expectations for fast and personalised government services are just a few of the challenges you face…In this new economy we need Australians to be more innovative, more entrepreneurial and government should be the catalyst… Now, I talk a lot about people being this countryʹs greatest asset because the next boom is the ideas boom…I want the APS to be part of that boom. Thatʹs why one of the pillars of our innovation agenda is government as an exemplar. I want you to be bold in your thinking. I want you to lead by example.”

But is government prepared to be the catalyst and the exemplar? The Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis (IGPA) has just completed a research project funded by Telstra which interrogates this question through a survey of digital thought leaders working at the heart of the change process in Commonwealth, Territory and State government. The findings that follow are organised around four key questions. What are the drivers of digital change? How is government responding? Where is government acting as a digital exemplar? And, what are the main barriers being confronted? The findings make for interesting reading.

What are the drivers of digital change?

All of our respondents identified prevailing macro-economic conditions as a stimulus to digital change. This was variously associated with ‘cost containment’, ‘doing more with less’, the ‘austerity-climate’, ‘getting best value’, achieving ‘productivity gains’, ‘returning the budget to surplus’ or ‘the next logical step after fiscal consolidation’. The majority were of the view that austerity provided fertile conditions for digital change, but that in the short term it also complicated the investments needed to achieve medium to long-term efficiency gains.

Notably most respondents recognized that the pace of digital change had accelerated as a consequence of the emergence of a strong political agenda fostered by Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull ‘who gets technology and the opportunities that it provides for improving problem-solving in a period of fiscal constraint’. At the same time there is also overwhelming evidence of the need for government to respond to a culture shift in Australian society where consumerisation has heightened citizen expectation for quality on-line service interactions ‘any time, any place, anywhere’ and this is particularly evident from the following data:

- 2.8 million people have accessed myGov to lodge online;

- more than one million citizens lodged online tax returns on myTax in its first year;

- Over 5 million people have linked their MyGov account to the Australian Tax Office;

- 450,000 super accounts worth $1.9 billion have been consolidated online since 2014 and

- 1.2 million Australians have enrolled their voiceprint with ATO to verify their identity since mid-August 2014 (See: ATO, http://lets-talk.ato.gov.au/Digitalbydefault/news_feed/digital-by-default-consultation-paper-november (accessed 22 March 2016).

How is government responding?

Most of our interviewees acknowledged that this was a period of accelerated change or as one informant put it ‘Uber change’, where digitisation is enabling significant strides in the ways in which data is collected and analysed (‘data is the new oil’); where insatiable demand for quality services can be met (‘digital is a survival strategy – how else will we cope?’); and where government can play an important role in facilitating economic development and promoting Australian products (‘digital provides government with a more obvious role to play in facilitating economic development’).

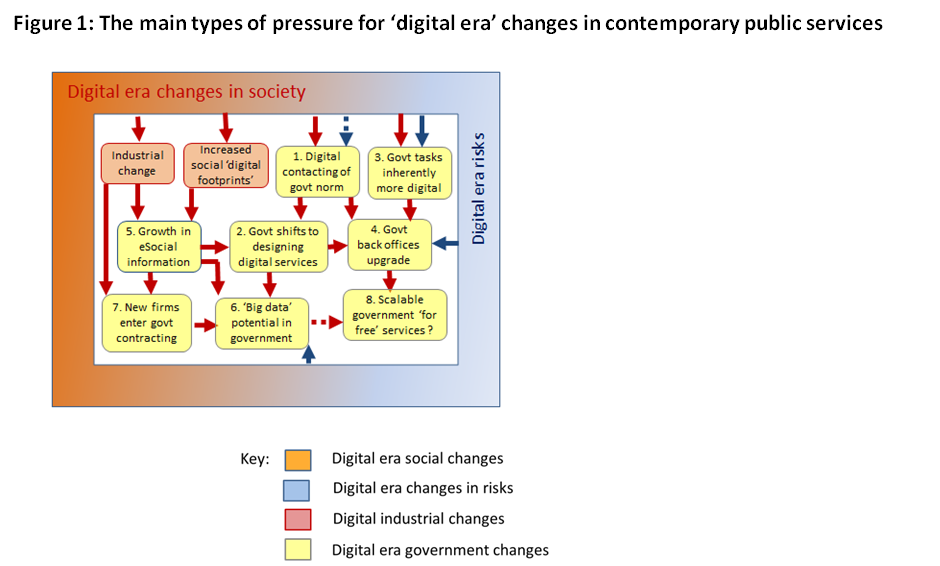

Yet relatively few interviewees’ felt that they had a comprehensive overview, and so we have compiled Figure 1, which shows the key pressures and trends pointed to by our interviewees as a whole. In the top left corner we locate the two external trends that interviewees saw as having most impact on government, namely the growth of new industrial giants such as Google, Facebook, Amazon and Twitter on the one hand; and the readiness of consumers to increasingly live their lives digitally and online, in the process making huge amounts of information about themselves available to commercial and civil society actors. As Figure 1 illustrates, these and other changes have precipitated some very substantial challenges for Australian public service agencies as a whole. By any standards the digital agenda here is a huge one. Yet the final component of Figure 1 in the right hand margin box stresses that ‘digital era’ risks have also grown. These include threats from cyber-attacks and e-security breaches; digital expansions in the competencies of criminals, terrorists and hackers; and scale increases in the scope of consequences if contemporary digital security or storage provisions are breached, deliberately or inadvertently.

Where is government acting as a digital exemplar?

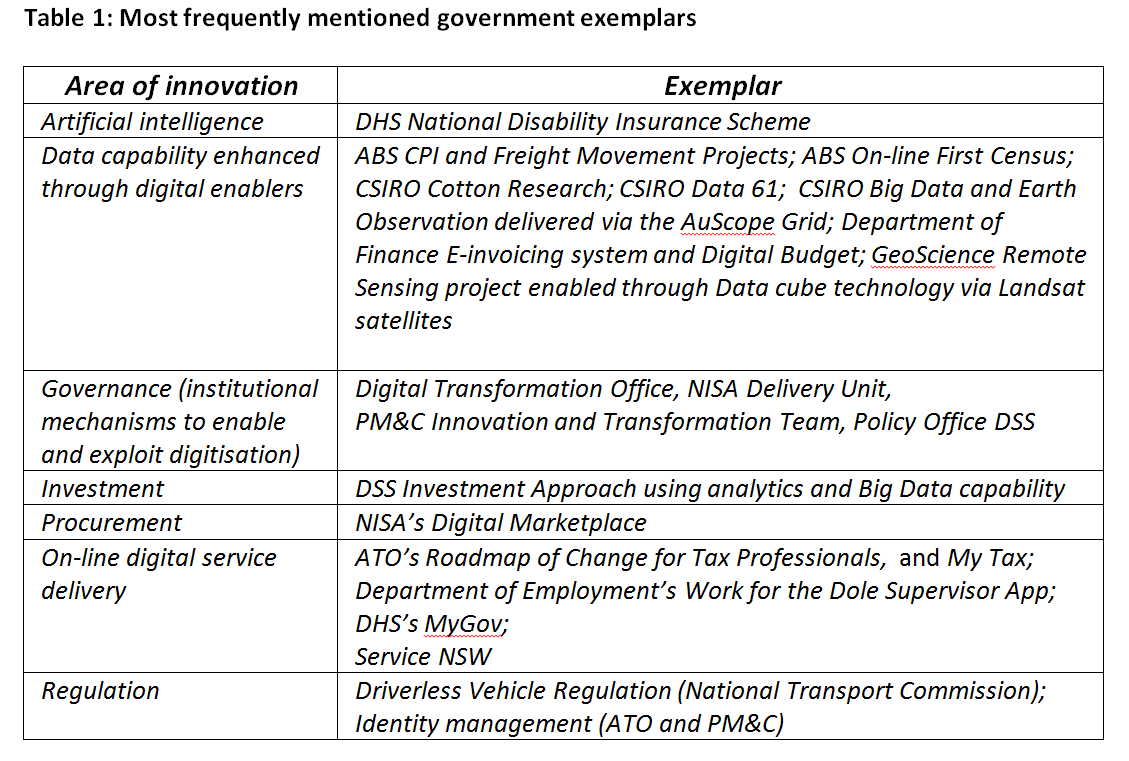

Many respondents pointed to examples of APS agencies acting as digital exemplars. Table 1 shows that the schemes most nominated cover a range of DEG reforms that are likely to attract significant funding in Budget 2016. The size of the agency, its history and core business and its proximity in relationship to the primary government agenda tends to inform the selection of examples. For example, the ATO and the Department of Human Services (DHS) have long histories of engagement in digital innovation due to the large number of transactions they conduct on-line and their potential for joining-up other service areas. Most agencies see significant potential for Artificial Intelligence in

enhancing citizen interactions with government and Big Data analytics for improving the quality of real-time decision-making. ATO’s Roadmap of Change for Tax Professionals is a good example of a high quality interactive on-line platform and CSIRO’s Data 61, and Big Data and Earth Observation project delivered via the AuScope Grid will provide a significant contribution to the generation of quality data for real-time decision-making. In addition, the creation of NISA’s Digital Marketplace will provide a ‘one stop shop’ for accessing digital capability.

What are the main barriers being confronted?

So what did our respondents perceive to be the main barriers to digital change? Familiar themes to those well versed in APS culture were raised mostly focusing on cultural barriers (e.g. a risk averse and digitally unaware policy elite), legislative barriers (e.g. privacy and procurement laws inhibiting ‘tell us once’ and ‘ask us once’ innovations), resource barriers (e.g. archaic budget rules) and capability barriers. The most significant of these is viewed to be the capability deficit which is commonly viewed to be the major barrier to digital change both in the public sector and in Australia more generally. The APS does not possess sufficient technology leadership at the Executive level service-wide to strategically manage and lead this scale of digital change. Departments with major digital projects face serious capability constraints in getting skilled staff. And profound changes are required at the tertiary education and graduate training levels to ensure fit for purpose digital capability. It appears that the need for STEM postgraduate education has reached crisis proportions.

Seeing digital

There is compelling evidence that digital change is transforming agencies with significant service delivery and data analytic functions in a radical way. Moreover, there is a strong current of opinion within the APS elite that there is a tangible difference to this process of change reflected in the strong strategic alignment between the Turnbull Agenda and the desire in the ‘Digital First’ and data driven departments to exploit advances in technology for more efficient decision making and service delivery. The Prime Minister has succeeded in motivating Commonwealth government to act as a catalyst and exemplar in digital change; he now needs to work his charm on the Australian public from the budget through to election time.

Professor Mark Evans is currently the Director of the Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis (IGPA) and Professor of Governance at the University of Canberra.

Patrick Dunleavy is Centenary Professor of Governance at IGPA and Chair of Public Policy at the London School of Economics.