Why political scientists should study anti-politics

In a post originally published on the PSAblog, Matthew Wood stresses the importance of viewing European anti-politics as more than ‘populism’

It seems pretty much unanimous among commentators that 2016 was the year of populism. Concepts clearly have a life of their own, they catch the mood of the times, float upwards and trip off everyone’s tongue easily. Brexit and Donald Trump have been lumped together as two unexpected political events caused by populism, for example. Are these happenings really the result of ‘populism’, ‘anti-establishment’ sentiment, or (as some claim) the renewal of right wing extremism?

One important job of political scientists is to subject these concepts to a bit more scrutiny, and see whether they actually capture what’s really going on. If they don’t then we should think about what concepts more accurately describe and explain the problems facing democracies today. Last week the PSA’s Specialist Groups on Italian Politics and Anti-politics meet with academics from across Europe in Turin to do exactly this. The key question is: how do we accurately characterize the ‘stress’ European democracies seem to be experiencing?

Why not just populism?

In this spirit, it’s important to examine whether ‘populism’ accurately describes why European democracies are under ‘stress’, or whether different concepts would be better. I think populism does capture a significant amount of what’s going on. Nigel Farage rallied what he called ‘the people’s army’ to vote for Brexit while Geert Wilders and Marine le Pen both claim to represent ‘the people’ against traditional political parties. But I don’t think this is enough to explain what’s going on.

Political scientists studying populism show the best definition is a political style of appealing to ‘the people’. It’s a very old concept, and politicians as diverse as Tony Blair and Nelson Mandela have been described in these terms. Its contemporary fit certainly isn’t perfect. As the New York Times noted, it is a poor fit even for the range of so-called ‘populist’ triumphs we’ve seen recently. In Italy the vote against President Renzi’s constitutional reform proposals was a vote to block a dangerous centralization of power in the executive – it was a vote against populism. The term itself,

What about ‘anti-establishment’ politics, a concept PSA Chair Prof Matthew Flinders has used? Again, I think this term has much to it. Anti-establishment sentiment is clear in opinion polls showing distain for political leaders. The so-called ‘left behind’ contributed towards the Brexit vote in the north of England, voting against an out-of-touch establishment. Renzi’s defeat was trumpeted as a victory for the Five Star ‘anti-establishment’ movement. But this trend certainly isn’t uniform. One of the most popular politicians in the UK at the moment, for instance, is Sadiq Khan, a ‘machine’ politician produced from the Blair-Brown years.

More generally, research shows there simply isn’t a desire for some radical form of ‘new politics’ where the public are directly involved in deliberation and decision making. Some politicians who’ve tried to ‘do politics differently’ – like Jeremy Corbyn’s attempt at changing PMQs to a radio phone in style dialogue with ‘the people’ – have fallen flat on their face.

The last, more harrowing term some have used relates what’s happening more to the ‘alt-right’; ugly far right politics, often associated with racism, xenophobia and even fascism. And again, there is value in this concept. In Poland there was a deeply worrying attempt by the ruling far right party to ignore the Polish constitutional court. We may yet see more triumphs for far right parties in Europe this year. But again the current trend hasn’t only benefitted to far right. In Austria the far right lost out in its bid to win the presidency, and in Portugal and Spain the left have been reinvigorated. Attitudes towards asylum seekers are also positive in some opinion polls, with support for cultural diversity in Sweden and Germany.

Anti-politics and the broader democratic problem

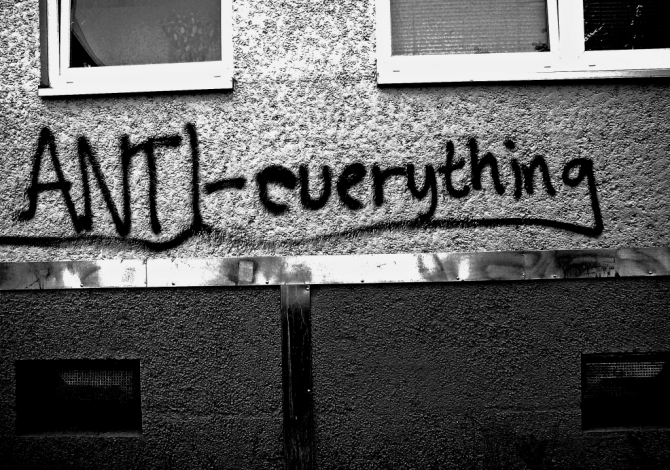

To think more broadly about the range of developments we’ve experienced recently, I prefer the term anti-politics. For me, anti-politics is an important term because it points to something emergent, something we don’t yet know in full, and something that could be beneficial to either left or right. It’s a concept that captures this feeling we have a vacuum in public life.

Last year we often heard commentators talk about a ‘vacuum’ that populist, right wing or anti-establishment figures have filled. We’ve heard about the ‘collapse’ of a liberal multilateral order, and the end of ‘neoliberal’ globalization. But what is this vacuum? Why has it emerged? Who made it open up and how might governments respond to it?

To understand what this ‘vacuum’ is, I think, we need to connect these specific political events with broader developments in western economies and societies. Democracy has always fed off a vibrant civil society, be it thriving businesses, bustling civil society and a vibrant culture.

This vibrancy has been on the wane for the past decade. Our high streets have become dominated by a small number of corporate chains, and start up and local businesses are increasingly pushed out by gentrification in our cities and extortionate rents. The so-called ‘gig-economy’ has created a sense of economic and social dislocation and displacement.

Meanwhile, Europeans have felt the full force of austerity measures that have local governments unable to provide very basic services. Governments struggle to stimulate economic growth and improve living standards (although they often claim they can to get votes – hence the populism). Recent research shows a widening gap between a global elite able to travel almost at will and the so-called ‘precariat’ stuck in low pay, low security jobs.

This has led to people becoming stuck in ‘bubbles’ – the most famous being in the social media world – where they socialize mainly with people they choose to talk to (often those with their same interests and worldview). All this marks a stark contrast to ‘mass’ democracy in the 1960s, 70s and even 90s, with relatively high social mobility and integration.

Thinking about our democratic ‘stress’ this way also makes some unexpected connections. For example, why have so many people viewed 2016 as a terrible year connected the deaths of important musicians, film stars and other celebrities with the rise of populism? Could this have something to do a sense of losing the mass ‘civic culture’ we once had? Music, art and theatre provide the cultural lifeblood of democracy, promoting innovation and engaged citizenship. Even ‘low’ forms of cultural subversion, like those David Bowie was well known for, are crucial lifeblood to public life. But if music, film and theatre become the domain of a cloistered elite, the arts become disparaged and pricey rents push entertainment venues out of business, what happens to our democratic culture?

Anti-politics encompasses this wider terrain, likening ‘politics’ to a well functioning representative democratic system, and pointing to its decline. The term suggests we’ve lost – or are losing – a broad culture necessary for representative democracy. We are losing economic mobility and security, losing a common and vibrant culture, losing social cohesion and mobility, and losing trust and faith in our politicians. Some could argue we’ve never had these things in the first place – and they might be right – but that doesn’t reduce the importance of understanding why we don’t, and what we could do about it.

Why Anti-politics Matters

Various terms have been thrown around to describe tumultuous events in the past year. They all have their benefits and drawbacks. Some point us down a narrow alley to focusing on political parties and their electoral strategies, others aim to broaden things out a little. I use the term anti-politics because if we’re going to properly understand what sort of democratic crisis we’re living through and how we might resolve it, we need terms that shift and challenge our thinking. We need terms encouraging political scientists to think and work with different professions – sociology, economics, geography, cultural studies, and so on.

As political scientists it’s our responsibility is to go beyond the obvious and straightforward in explaining political events. To do so we need concepts that accurately portray what’s going on, and also seek to delve into the deeper reasons for why we’re seeing the massive shifts in representative democracy that are happening right now. Anti-politics is helpful because it indicates something much bigger and multifaceted that’s going on in quite different but interconnected spheres of liberal democratic life. It’s not just limited to the rise of populist politicians, but worrying changes in our open and tolerant cultures and economies that make ‘formal’ representative politics work.

Anti-politics is the idea we’re seeing a transformation that is deep and profound in the way politics is organized and conducted. What replaces it may well be something dark and malicious. It might also though, be something positive, a new way of organising society, be it ‘deliberative’, ‘direct’, ‘monitory’ or something else. Anti-politics is useful because it’s ambiguous, contested, somewhat scholastic, but also compelling.

This blog featured on the Crick Centre blog, and can be found here: http://www.crickcentre.org/blog/why-political-scientists-should-study-anti-politics-europes-democratic-crisis-isnt-just-about-populism/