Election Trolling and Foreign Influence Campaigns

The indictments just handed down in the United States against 13 Russian nationals and 3 Russian entities presented for the first time a detailed narrative of the investigation’s understanding of efforts by Russia to directly intervene in the US election. The indictment shows a remarkable level of planning and activity which included extensive social media influence operations, staged demonstrations, payments to Americans to take part in activities, and even direct engagement with the Trump organisation to obtain assistance in organising demonstrations. In official documents, these activities were termed “information warfare” (sec. 10C of the indictment). Furthermore, their social media operations were not amateurish trolling but evidence-based strategic communications. The strategies were developed based on fieldwork conducted by Russian operatives who entered the US under false pretences, they monitored the effectiveness of their communications and updated strategies, and they operated with a budget of over $1 million (USD) per month.

Left out of this indictment is a sense of how Russian trolls operate and exert influence. It is important to understand how Russia sought to influence the US elections for two reasons. First, they did not stop after the election. Indeed Facebook notes that most of the impressions on Facebook ads purchased by agents linked to Russia’s Internet Research Agency (the entity which carried out the social media operations) occurred after the election. Second, as the recent concerns about foreign influence operations in Australia demonstrates, the United State is hardly the only target and Russia is hardly the only perpetrator.

While the indictment brought by Mueller contains information which was likely obtained through covert operations – items like internal documents and emails sent by employees – foreign influence operations are by nature “noisy” and by necessity carried out in the open. Therefore, a lot of what they do and how they work are things we can infer through the public trail they leave. This has somewhat been hampered by the fact that the accounts in question have been suspended or deleted which makes it difficult to go back and retrieve the data unless one had collected prior to that point. On the Twitter side, we have data on the tweets produced by accounts which have been linked to the Internet Research Agency as these accounts were identified by Twitter and made public during a hearing with the US House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. Using those data, over 200,000 posts by 454 accounts were extracted prior to their deletion and this data has been made available by NBC News in the United States.

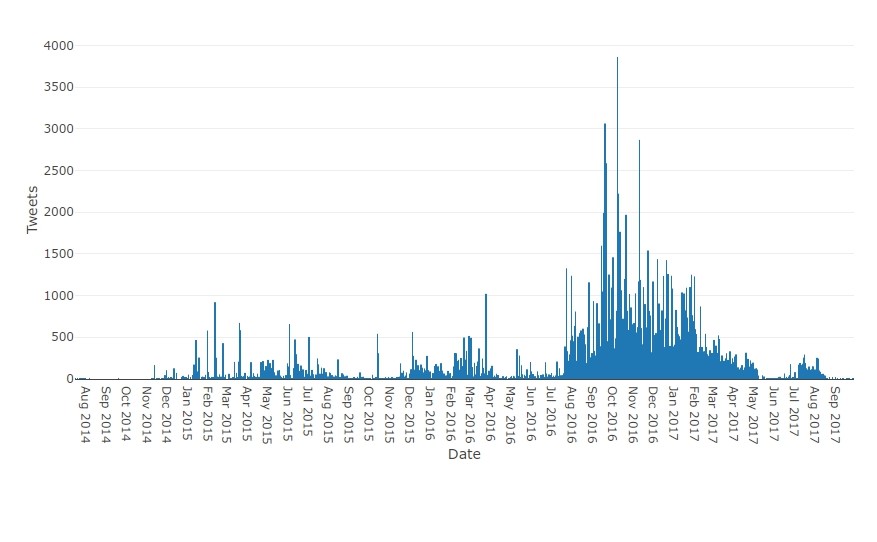

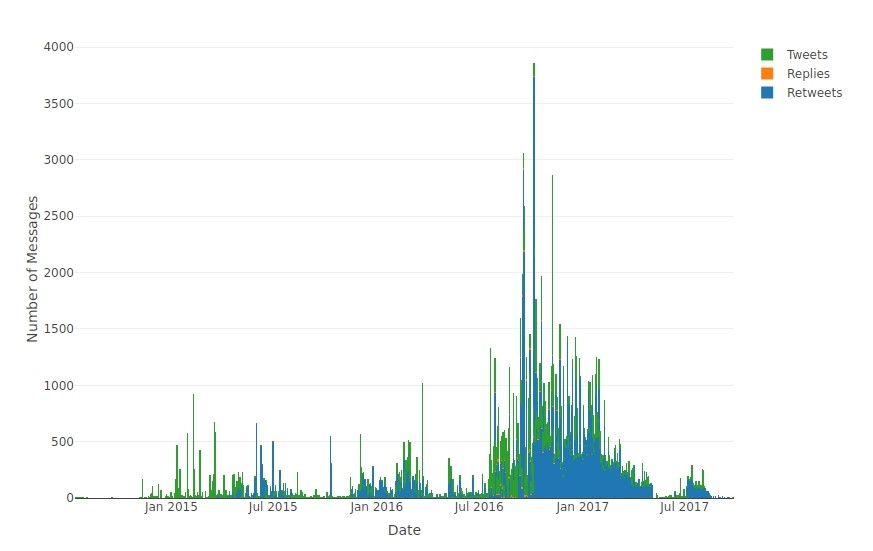

These accounts have been active since a period well before Trump’s announced run for the presidency on June 16, 2016, a point Trump himself has noted. Whether that exonerates him or incriminates him having planned this all along with Russian officials is another matter and not addressed by the indictment. This chart shows the number of posts per day made by accounts identified as working out of the Internet Research Agency between July 14, 2016 and September 26, 2017, around the time when employees there had discovered “the FBI busted our activity” (Indictment, Sec. 58d).

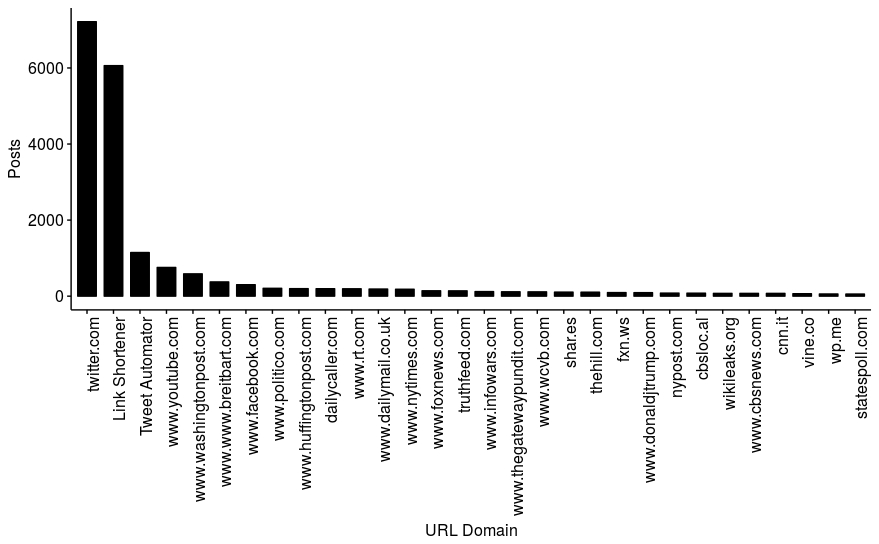

There are a lot of different strategies which have been used to cultivate influence so it is important to understand what these accounts were doing in the lead up to the election. First, ten percent of accounts with user descriptions (34 of 339) had news, usually local news, in their Twitter profile descriptions. These accounts could present themselves as alternative news sources. In addition, these accounts did not push predominantly Russian sources of news in the materials they linked to. Apart from Russia Today, they mainly focused on sources which would be more familiar to Americans, particularly alt-right information sources such as Breitbart and the Daily Caller. Several of these accounts also maintained blogs which they linked to in order to expand on their thoughts.

The links to Russia Today should not be overlooked for two reasons. First, sources like Russia Today and Sputnik News are often used to “launder” information from dubious sources and make it more mainstream. Second, the Russian trolls from the Internet Research Agency were more likely than average users to link to Russia today so this was a source pushing those narratives on social media. This is significant as Russia Today is considered a foreign influence agent by the US Department of Justice. While the most common link domain is Twitter itself, signifying quoted tweets, link shorteners and automated tweeting platforms mask the origins of the linked material. Link shortener tweet URLs were even masked from Twitter’s automatic link expanders (some were not and those were included in the totals for their domains) which is consistent with links to domains which closed quickly after their creation. Beyond that, the linked sources are sources which would be relatively familiar, particularly to persons who feel rather alienated from politics and identify with the alt-right.

In terms of the kinds of tweets these accounts made, their function shifts over time which shows changing strategies between their start up phase, the primaries, and general election. Early on we see a lot of original tweets which I, below, suggest may be part of a strategy of rapport building and generating a following, and later, there is a much greater emphasis on retweets. Apart from the ease of retweeting others, it shows that the strategy here is to amplify selected American voices as a means of legitimating, often divisive themes dealing with race and religion. Many of the Internet Research Agency accounts would retweet the same tweets to raise its prominence.

How Might Russia Have Tried to Move Voters?

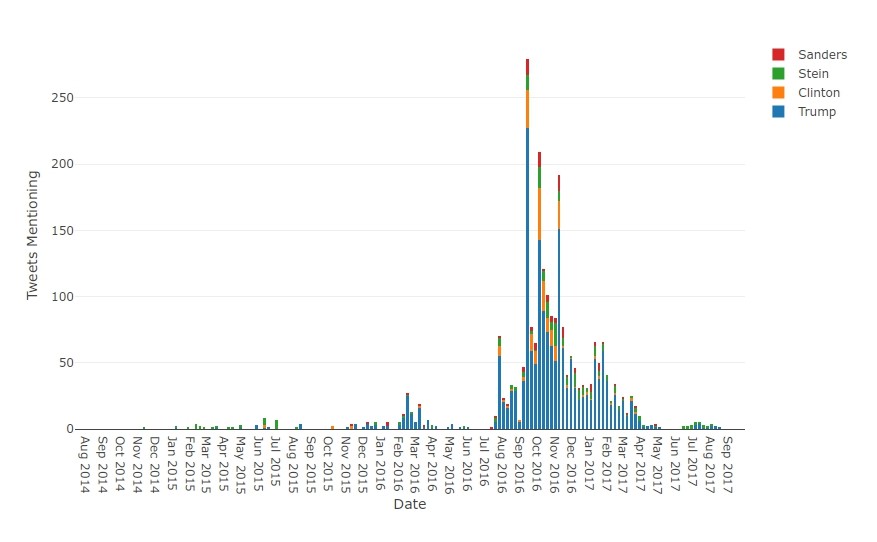

Mentions of any of the candidates were scant until the election got under way and then they went all in for Trump.

Looking at the mentions of candidates (by name or by Twitter handle) by the Internet Research Agency “trolls”, it seems their support for Sanders, mentioned in the indictment, came mostly during the general election as a means of suppressing Clinton’s support. Meanwhile, Stein figures in these data from quite early on – raising additional questions about what she may have been doing while in Russia before the 2016 election.

Were they were doing during that time? One of the ways in one can exert influence is to build a following online by getting persons to identify with you. We see a lot of that in the tweets during this period which aim at building rapport with people. Some of the early tweets include various maxims for living: “why give second chances when there are people waiting for their first?”, “True strength is keeping everything together when everyone expects you to fall apart #quote #true”, “Don’t go into business to get rich. Do it to enrich others. It will come back to you”, “Some days you’re a bug, some days you’re a windshield”. There are eleven references to the series Mad Men which ended in early 2015, eight coming during that time, reflecting on the series. Another user regularly retweeted viral Kardashian gossip. These tweets have a serious function: research shows that the opinions that flow through our networks of friends and family can play a decisive role in decisions about who to vote for or whether to vote at all.

Beyond mobilization, by flooding social media spaces with these messages, they can engage in “priming” which shapes the contours along which persons think about politics and engages political life. Additionally, as the who who is speaking is consequential for the meanings of statements, the fact that these accounts pretended to be Americans with particular fabricated backgrounds allowed them to be more persuasive and reach critical audiences than they otherwise could be. Here, persuasion and identity become intertwined: by claiming to be members of particular racial groups or supporters of various causes, they can use that deception to move others who think they are like them. These influence operations work by pretending to identify with their target audience and using aspects of their everyday life concerns to move them to act in the interests of the foreign principal. This is has historically been the aim of Russian influence operations, also known as “active measures”. One the more telling examples of this is when one of the more prolific and popular accounts run out of the Internet Research Agency changed its profile description to, “I’m not pro-Trump. I am pro-common sense”. Many of the tweets contained references to “common sense” as well.

What are the Consequences of Foreign Influence Operations in 2016 US Election and Beyond?

Specific changes in this indictment as well as the consensus of the US National intelligence community was that the election of Donald Trump served Russia’s strategic interests. That fact has surprisingly raised little alarm in Trump’s party, a party which has been otherwise known for its patriotism and serious about national security. More generally, these operations have aimed to sow discord; delegitmize institutions and democratic norms; systematically distort communications, which undermines democratic deliberation; and subvert collective capacities for problem solving by treating all aspects of governance through a political rather than policy lens. The Hamilton 68 dashboard is regularly updated with the latest themes pushed by Russian Twitter bots. Bots flood social media spaces with particular lines of messaging to create a false sense of the prevailing distribution of beliefs about a subject. Minimally, that can influence what people are talking about as a vehicle for agenda-setting, though it has a stronger impact on the algorithmic aspects of platforms, promoting trending topics. Trolls can engage in a more personal way, strategically intervening at decisive moments.

The participation of trolls and others under false identities distorts the range of opinions articulated and obscures their interests in the debate. In the US case, many of these messages questioned the legitimacy and honesty of any and all political figures as well as the media. They emphasised racially divisive themes and on Facebook organized demonstrations based on divisive themes which inflame religious tensions. These actions reduce the capacity for persons to come together to address common problems. For these reasons, active measures represent a grave threat to the politics and governance of democratic political systems.