Will A Marriage Equality Ruling Cause Public Opinion Backlash?

As the Supreme Court nears a ruling on marriage equality in Obergfell v. Hodges and the related cases, some publicly express a concern that if the Court moves too far too fast, the public will become too furious. Claims that public opinion backlash should be feared – that is, progress will lead to a surge in anti-gay public opinion, are the foundation of a cautious and slow approach. Even progressive Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg expressed this concern through a nod to the abortion fight. From the bench, Justice Kennedy reflected on the time lapse between major events as desegregation emerged. Who should appropriately enact change is another dimension of the “go slow” argument. For instance, John Bursch, an attorney for the four states opposed to marriage equality, argued the Court should defer to the voters to define marriage while Justice Scalia made the same argument to plaintiff’s counsel Mary Bonauto.

Claims of inevitable backlash and claims that voters have the right to vote on the rights of others have long been used to discourage the pursuit of equality by traditionally disadvantaged groups. We are most concerned with the role of public opinion since it plays a central role in democracies. We define backlash as a sharply negative and enduring shift in public opinion. Backlash occurs in response to new policies implemented through legislatures or courts (e.g., D’Emilio 2006), or even through non-policy events such as the election of minorities (Lipset and Raub 1970; Haider-Markel 2010). While the backlash story has persevered, finding empirical evidence of backlash in public opinion backlash is difficult. So, does public opinion backlash actually occur? Should the Court slow down and defer to the voters or risk a furious public?

Using on-line survey experiments, we test how and among whom backlash might be triggered. Subjects were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk. We sought to identify which citizens would lash back, how backlash could manifest (e.g., changed issue position, increased issue intensity, or both) and whether backlash is more likely in response to courts or legislatures. We surveyed 2,402 subjects over twelve days. Once they answered a pre-test about basic demographic and opinion questions, they read a news story treatment then took a post-test. The post-test presented questions about political knowledge and attitudes towards gays and lesbians.

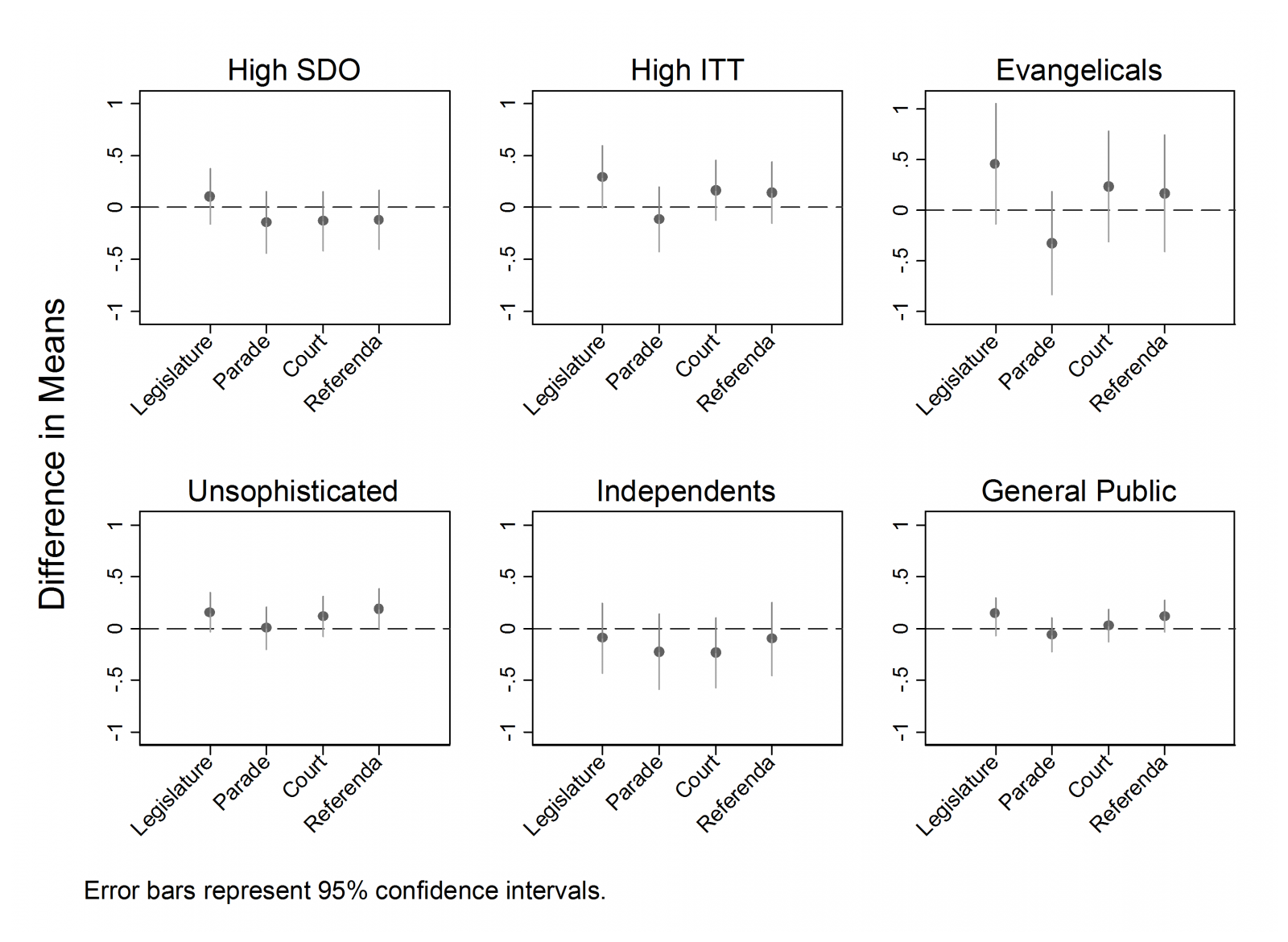

Randomly, the subjects were assigned either one of three treatment stories or a control story. The treatment stories contained a fictitious news vignette about gay rights in Oregon. These included a story of a state court legalizing gay marriage, a state legislature legalizing gay marriage, a non-policy story about a gay pride parade, and a story about gun control policy. Subjects knew they would be asked about the stories, and the follow-up questions demonstrated that they read and understood the stories. We identified the groups that existing research suggests might be likely to experience backlash— Evangelical Christians, individuals who score highly on an index of questions that ask about perceived threat (ITT), or individuals who might lash back due to challenges to one’s status or high sense of social hierarchy (SDO)—to determine if backlash might be more intense among these groups. Large and negative differences across conditions would indicate backlash. The difference in views toward gay marriage between the various treatment and control groups are in Figure 1 here:

Figure 1. Difference in Support for Gay Marriage (Treatment vs. Control)

The experimental results are startling—there is no evidence of backlash among any sub-group or among all respondents as a whole. In every case, the difference between the stimulus and control conditions approaches zero. Why? To test the possibility that policy changes in Oregon, our setting for the vignettes, might be insufficient to induce backlash, we conducted a second experiment. In June of 2013, we “arranged” for the US Supreme Court to issue opinions in two major gay rights cases on the same day: the ruling against Proposition 8 (Hollingsworth v. Perry), which extended marriage equality to California, and the decision that the federal Defense of Marriage Act was unconstitutional (United States v. Windsor). These high profile opinions made the expansion of gay rights salient and therefore should have provided a significant threat to the status quo for those people who might succumb to backlash.

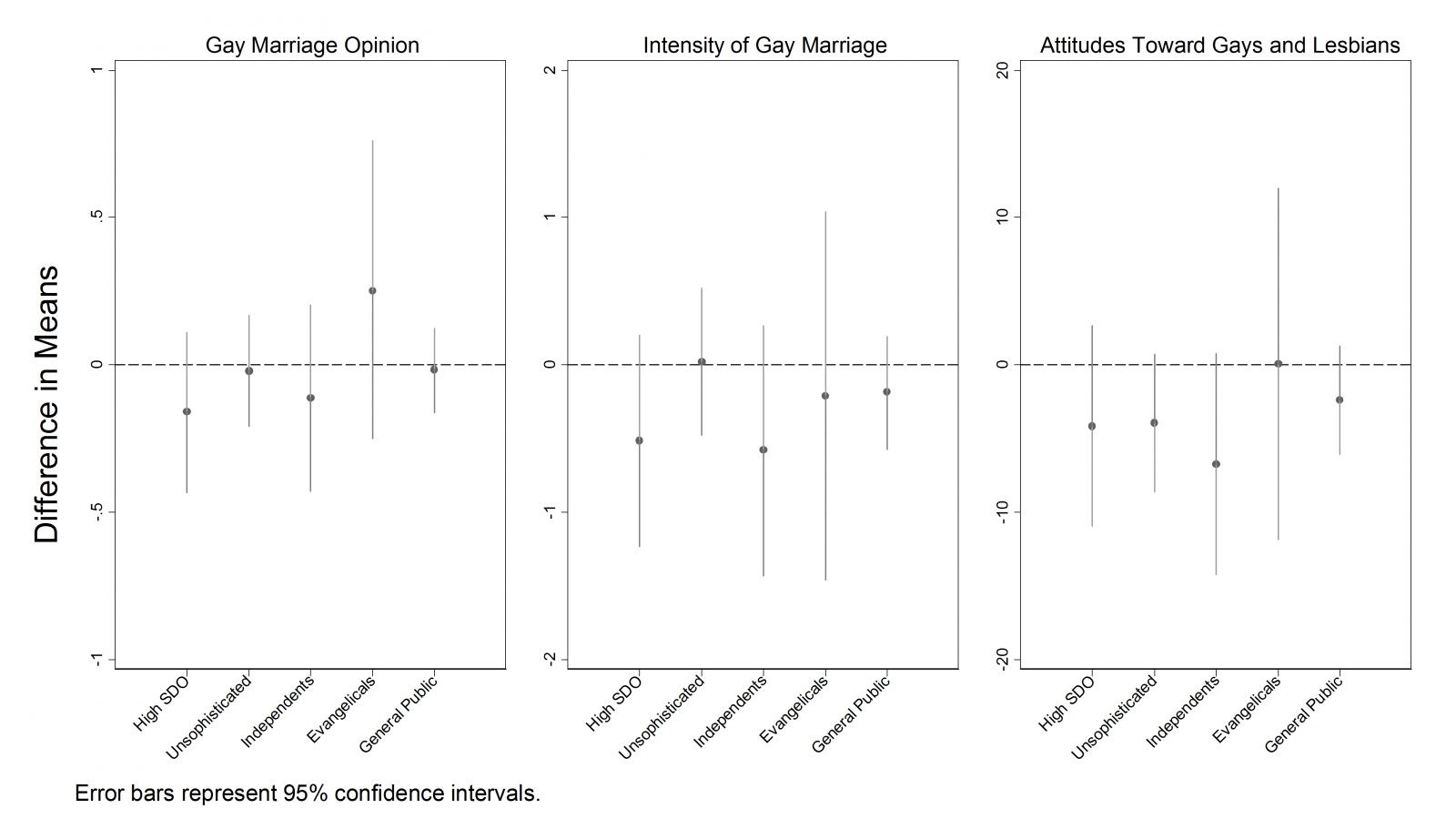

We re-administered our control condition (about gun control) beginning the day after the decisions to test whether the opinions led to backlash. Backlash can be revealed by subtracting support for same-sex marriage for subjects administered the control condition before the Supreme Court decisions from the support of those subjects administered that same condition after the hearings. In this case, backlash would be indicated by large and negative differences. Figure 2 presents these results.

Figure 2. Differences in Ratings Before and After Supreme Court Rulings (Gun Control Only).

Again, our results are inconsistent with backlash. Despite perhaps the strongest stimulus possible with actual policy implications for citizens in every state, and ubiquitous media coverage of the rulings, the magnitude is tiny and we find no difference in opinion on gay marriage, intensity of feelings about gay marriage, or warmth of feelings, before versus after the rulings.

Conclusion: Contributions and Broader Impacts

Over fifty years after Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail—a response to Alabama clergy who urged blacks not to march for equality, and to instead wait for the courts to grant them civil rights—some opposed to the expansion of equal rights now urge the courts to go slow. The fear of public opinion backlash—the primary basis for these claims—is not a valid reason to go slow. We find no empirical support for the claim that opinion backlash will occur on the issue of gay marriage. The Court need not fear choosing between democracy on the one hand and liberty and equality on the other.

References

- Bishin, B. G., Hayes, T. J., Incantalupo, M. B. and Smith, C. A. (2015), Opinion Backlash and Public Attitudes: Are Political Advances in Gay Rights Counterproductive?. American Journal of Political Science. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12181

- Haider-Markel, Donald P. 2010. Out and Running: Gay and Lesbian Candidates, Elections, and Policy Representation. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press.

- Lipset, Seymour M., and Earl Raab. 1970. The Politics of Unreason: Right Wing Extremism in America, 1790-1977. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.