The Importance of Continuous Sense Making in Crisis Management: The Case of the Euro Crisis

From the end of 2009, the Euro zone leaders have been struggling to find a common solution to the Euro crisis. The endless talks over the years between the finance ministers and Heads of State and Government have shown how dramatically different the parties make sense of the crisis. Despite the heavily fought agreement to start negotiating a 3th bail-out, hopes that it will bring a definite resolution to Greece’s problems have all but vanished, and predictions that a “Grexit” will happen continue to ebb and flow.

Looking back at the outcomes of our recently published article ‘Making sense of the Euro crisis: The influence of pressure and personality’ in the journal West European Politics, the lasting impasse in the negotiations between the European member states on the Greek situation does not come as a surprise. In our article, we argue that sense making is one of the most crucial phases in transboundary crisis management. Sense making is the phase in which leaders question, consider and define events. The aim of this is twofold: first, to insure that core decision makers ‘get a firm grasp on what is going on’, second for leaders to develop a clear idea of ‘what might happen next’ (Boin et al, 2005: 140).

Sense making is crucial in any crisis situation because it helps leaders clarify their underlying assumptions on how the world works and contemplate the value of different solutions before decisions are actually made. In case of transnational crises, part of the sense making should also have a common character to create a mutual understanding of a situation or reveal where irreconcilable differences in view lie. Moreover, although sense making is often portrayed as one of the earlier phases in crisis management, in reiterated decision making games associated in lasting crises, it should be a continuous process.

In our article, we ask the question to what extent leaders’ personality traits and the (economic) pressure they face affect the nature of their sense making. To do this, we examined six European Heads of State and Government (Merkel, Sarkozy, Balkenende, Leterme, Papandreou and Zapatero) during the early stages of the Euro crisis (2009/2010). We find that the extent to which leaders perceive the crisis as threatening, complex, urgent or their sole or shared responsibility can be partially explained by personality traits, in particular a leader’s belief in the ability to control events and self-confidence. To a lesser extent, our findings also suggest that differences in economic pressure influence leaders’ sense making of the Euro crisis (van Esch & Swinkels, 2015).

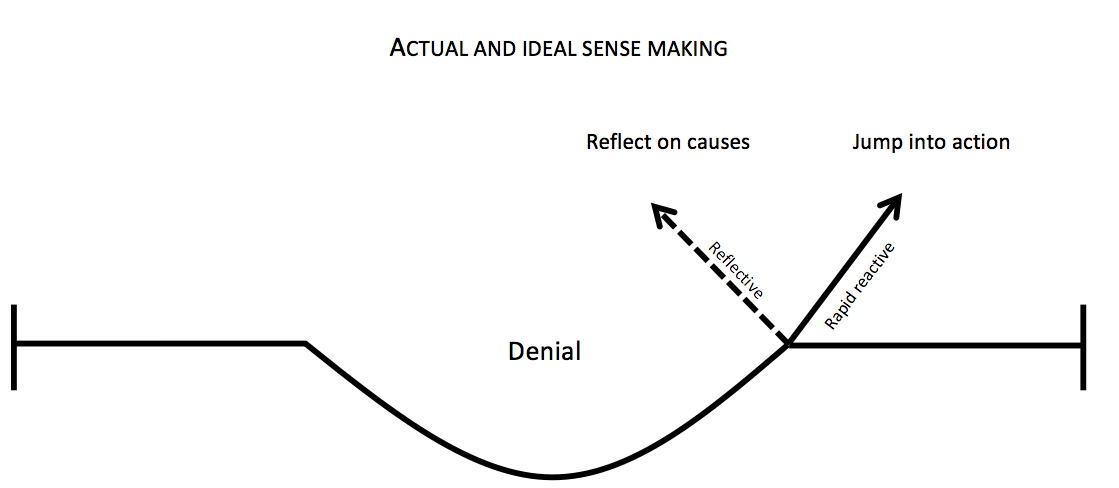

Even more interesting in the context of recent events, however, are some of the sub conclusions we arrive at. We find that after a period of denial of the problems, the European leaders arrive at widely different diagnoses of the crisis. In addition, we discover that rather than to delve into the roots of the crisis, they are more likely to jump straight into discussing possible solutions and the role the different member states and European institutions should play (see figure 1). In other words, leaders neither engaged in a thorough contemplation of what they perceived as the cause of the crisis or the assumptions underlying their preferred solutions, nor did they engage in any shared European sense making.

Figure 1: Euro leaders Jumping into Action

Let us start by putting these oversights into perspective and acknowledge that sense making is extremely difficult. Collective sense making in case of highly complex, transboundary crises like the Euro crisis is even more difficult. The threat, complexity and calls for urgent and decisive action that accompany crisis situations makes it tempting for political leaders to skip crucial parts of the sense making effort and quickly jump to discussing possible solutions. Jumping to conclusions may also feel more efficient at first. However, there is a grave danger of it backfiring in the end, as is illustrated by the ongoing Euro crisis.

Firstly, the seemingly endless series of high political summits devoted to solving the crisis over the last five years show that it is extremely difficult to find agreement on measures to be taken leaders are not on the same page with regard to the causes the crisis. Proposals on taxes, pensions, institutional reform, investments and austerity taxes like those put forward by the Euro zone countries (see figure 2) as well as the objections of others make sense only when the fundamental worldviews and ultimate values in which they are rooted are being exchanged and mutually understood. Moreover, when radically different perspectives exist on the workings of the economy without addressing their fundamentals, negotiations will be dominated by murky clashes over implicit assumptions and values rather than by constructively and respectfully finding a way through the maze of the different perspectives towards a compromise. To safely navigate through a minefield, one simply needs to know where the beacons and bombs are.

|

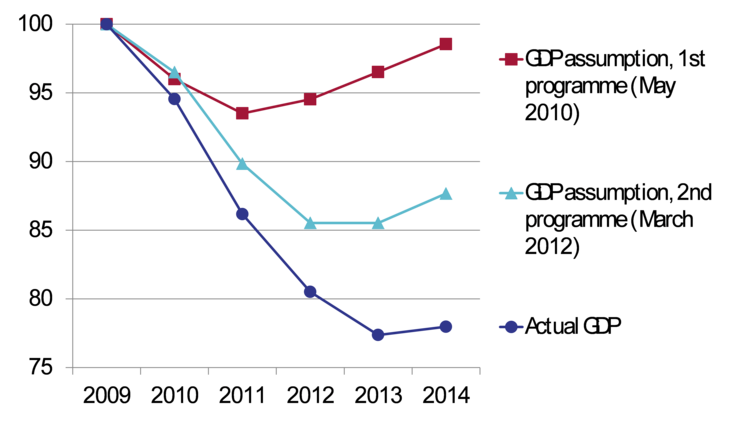

1. Streamlining VAT |

Figure 2: Conditions for Starting Negotiations on the Third Greek Bail-out as Proposed by the Euro group

Secondly, in complex long-term crises, like the Euro crisis, when uncertainty prevails and even the worlds’ best and brightest economic and political minds offer contradictory advice, it is imperative to engage in sense making on a continuous basis. To enable this, leaders must acknowledge the potential fallacy of their assumptions and causal beliefs to avoid getting cognitively and electorally stuck in the frame they adopted at the start of the crisis. This pattern is for instance visible in the stance of the German Chancellor Merkel who is still, as she was at the start of 2010, advocating tough austerity measures and full reimbursement of the Greek loans even though evidence is mounting that the economic assumptions underlying such an approach is flawed (see figure 3). This has severely limited the flexibility needed to find a European compromise. Leaders will not be able to arrive at evidence-based shared crisis management when they do not rigorously and continuously scrutinize their causal beliefs and adjust the policy instruments they propose accordingly.

Figure 3: The Assumptions versus Outcomes of the Greek Austerity Program (in terms of GDP)

As our research suggests, skipping the ‘causal’ part of the sense making phase may be a common phenomenon in political crisis management. However, it poses serious threats to efficient decision-making and is likely to lead to deadlock later. The negotiations on the 3th bailout of Greece show that without thorough common sense making an agreement can only be found by exercising naked power. This is highly problematic in a European context that aims to be democratic and is built on the sovereignty of member states. Moreover, as the public backlash to the negotiations shows, it may incite a severe and further decline in legitimacy of the EU among the European people.

The findings of our study suggest that leaders’ personal traits and context affect the nature of their sense making. This raises the question whether these factors may also interact to hamper or stimulate how complete and thorough their sense making efforts actually are. Given the immense social repercussions incomplete sense making during crises may have, further research into this topic should be at the top of the academic agenda of transboundary crisis management.

References

- Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., Stern, E. and Sundelius, B. (2005) The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Esch, F.A.W.J., Swinkels, E.M. (Published online February, 2015), Making sense of the Euro crisis: The influence of pressure and personality. West European Politics, DOI: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1010783

- Darvas, Z. (2015), Is Greece Destined to Grow? Breugel.org, http://www.bruegel.org/nc/blog/detail/article/1647-is-greece-destined-to-grow/