The Emotional Style of Populist Politics

Populism has been on the rise in many parts of the world. Populism emerges as a response to people’s feelings of having become sidetracked by “the system”. They are angry and frustrated, because they experience that politicians and their ‘stakeholders’ do not listen to them or take their anxieties seriously, except when an election is looming.. Furthermore, they think that politicians have become thick as thieves and that it really doesn’t matter any longer whom you are voting for. There are several good reasons why people display rapidly growing negative attitudes towards not only politicians but also the formal institutions. One is that inequality is spiralling. For example, Oxfam reports that the richest 62 billionaires have the same amount of wealth as 3.6 billion people; and inequality.org shows that the top 0.1 percent on the income scale in the USA are taking in over 184 times the income of the bottom 90 percent. Another contributing reason is globalizing neoliberalism, pushing parties towards the forming of a cartel, keeping all “economically irresponsible” parties away from the contest of becoming the party in government. The domination of the cartel party has made the goals of politics self-referential, professional, and technocratic: internal competition is decided only by concerns for efficient and effective management of policy and the population. Furthermore, debacles at election time usually concern the about 3% of policies that have not yet been decided on in the cartel. They are hugely capital intensive and assume the form of an audience or spectator democracy, providing spectacle, image, and theatre with very little policy substance.

Populism is first of all a moral response to globalizing neoliberalism and its uncoupling of elite democracy from popular democracy (Mair, 2013; Tocqueville, 2010; Wolin, 2006). It typically involves three interrelated attributes: (1) an anti-establishment disposition or demand (Laclau, 2005), articulated by a counter elite on behalf of ‘the people’; (2) a claim to exceptionalism by a morally indignant leader promising to make the battered home of “we the people” whole, comfy and safe again (Müller, 2014; Torre, 2014); and (3) a strong, decisive and morally driven leader, who claims to be the people’s voice. Hence, populism is for and with a special and energetic people, but certainly of and by the people. Those people who do not see the light and morally and actively support the great leader are not regarded as part of the homogenous people at all. Thus, citizens are thought incapable of reconnecting themselves with political authorities, perhaps a fool’s errand anyway. The people cannot themselves heal popular democracy, but depend on a leader who will “drain the swamp” which characterises the political establishment. .

The leader’s almost “God-like” intuitive and emotional relationship to the people is at the heart of populism. Previous research has focused on the charismatic bond which forges an emotional tie between populist leaders and their supporters (Arato, 2014; Madsen & Snow, 1991). Less attention has been paid to the emotional content in the appeals of the populist leader (Moffitt, 2016). The populist approach tends to be more emotional as a rejection of the technocratic rationalism of neoliberal discourses. This contrast is brought to a head in the current campaigns between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton in the United States with the emotive performance of populism against the first female candidate for a major party who seeks to balance her gender and a defence of the rational, neoliberal establishment.

The 2016 contest for the White House has been one of the more dramatic presidential races in recent memory given the personalities and accusations which transcend the conventions of decency and at points a near civil war within Republican Party. And with just over a week to go, the FBI made an unprecedented announcement that it had reopened an investigation into Clinton’s handling of email while Secretary of State. And despite the sensation we have been on a “poller coaster”, in historical terms, the polls have remained quite stable in large measure due to resurgent partisanship (in fact the public polls we see may be more variable than voting intentions are actually shifting).

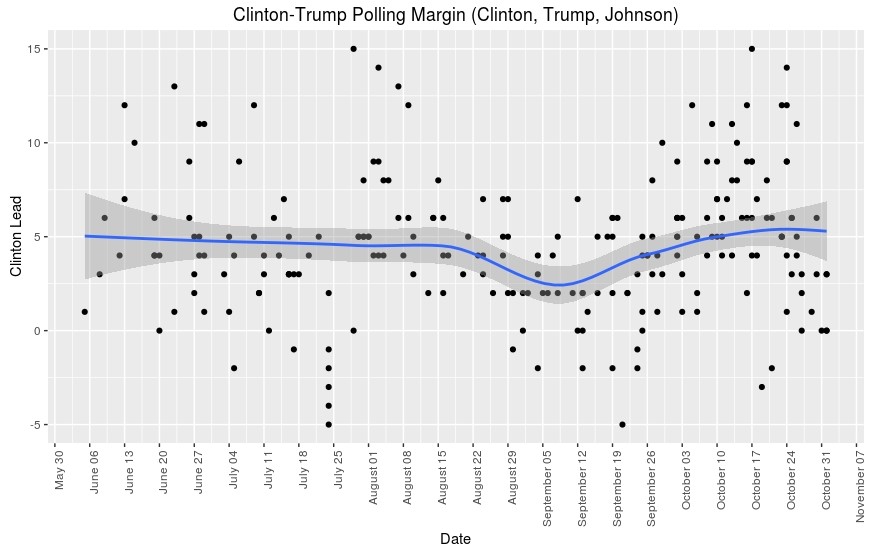

In fact the polls have barely changed since June 2016. Using the polling margins for a three-way race, with a loess smoothing line, Clinton’s margin is slightly ahead of where she was in June. The level of dispersion reflects the fact that there are a lot of polls out there and many will indicate a tight race, others will indicate a larger lead, depending on how they construct their samples and likely voter models. The latter can be crucial as different models can lead to highly varied readings of the same data.

The relative evenness of the polling data belies the emotional tone of the campaign, in particular from the candidates. We can get a better sense of the candidates’ communications of emotion by looking at their least filtered statements, those they release on social media. There is evidence that Trump’s tweets are a relatively direct expression of Donald Trump himself. He seems to personally use an Android device and these tweets tend to contain more anger than other tweets and even during the day, most of his tweets are dictated even if he does not directly post them. For Trump, his Twitter account is a means to convey his authenticity. Clinton on the other hand is known to have her tweets, even those signed “-H” to indicate it personally came from her, may be the product of Clinton’s communication team at least in some cases, and only run by her for approval.

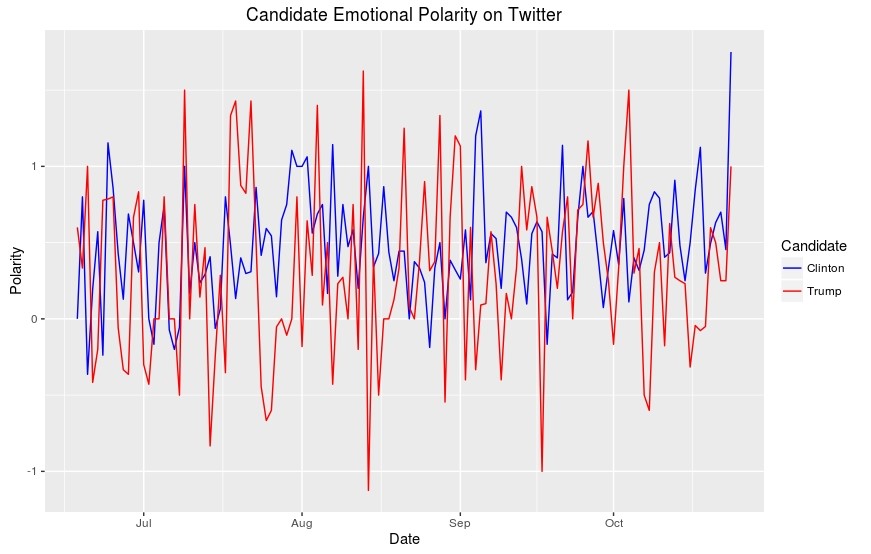

These differences as well as differences in temperament show up in the emotional polarity of their tweeting. There have been eight basic emotions identified: anger, sadness, fear, disgust, joy, surprise, trust, and anticipation. The first four are negative and the last four are positive. Using the syuzchet package in R, we can calculate the emotional content of tweets looking at their overall emotional polarity using a dictionary of emotions. Individual words may point to more than one emotion therefore we use a measure of positive and negative emotions contained in the package to not double count certain terms. The average polarity of tweets aggregated daily is presented in the following figure.

The polarity of Clinton and Trumps Tweets are largely inverted: when one candidate expresses positive emotions the other negative signalling a high degree of reactivity to each other. However, Trump’s emotional expressiveness is subject to wider swings. His individual tweets range from a +7 to a -6 compared to Clinton’s +8 to -4. The standard deviation of Trump’s tweets aggregated daily is 0.56 compared to Clinton’s 0.34 showing on average Trump is prone to wider mood swings. This highly emotive communication style is consistent with Trump’s style of interaction with his supporters where positive and negative emotions are taken as a sign of his authenticity, compared with Clinton’s more highly managed image (for better or worse, the managed image may well be an authentic expression of how Clinton understands herself).

These data are consistent with an understanding of populism centred around the relationship between a people and the leader. In the case of Clinton who has campaigned as an establishment candidate drawing contrasts in her experience and understanding of policy with Trump’s lack thereof. Trump’s emotional swings are part of the populist appeal: he brands himself as the billionaire his imagined people can identify with and wish to become. The managed image Clinton presents seems artificial compared to the showman who expresses emotions supporters can identify with. The latter gives the sense of a personal connection between the leader and followers whereas the former is symptomatic of the wider abyss between politicians and citizens. Because emotional affinity is no substitute for popular content as far as democratic governance is concerned, that abyss cannot be traversed through populism. As Tocqueville warned, a growing gap between citizens and their leaders is fertile ground for the emergence of democratic despotism at the hands of a populist political figure. Closing that gap requires finding new ways to connect citizens and authorities in ways which are consequential for political life.

References

- Arato, A. (2014). Political Theology and Populism. In C. de la Torre (Ed.), The Promise and Perils of Populism: Global Perspectives (pp. 31–58). Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- Katz, R.S. and Mair, P., 2009. The Cartel Party Thesis: A Restatement. Perspectives on Politics, 7 (4), 753–766.

- Laclau, E. (2005). Populism: What’s in a Name? In F. Panizza (Ed.), Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (pp. 32–49). New York: Verso.

- Madsen, D., & Snow, P. G. (1991). The Charismatic Bond: Political Behavior in Time of Crisis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the Void: The Hollowing Of Western Democracy. London ; New York: Verso.

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Müller, J.-W. (2014). “The People Must Be Extracted from Within the People”: Reflections on Populism. Constellations, 21(4), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12126

- Tocqueville, A. de. (2010). Democracy in America: In Four Volumes (Bilingual edition edition). Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc.

- Torre, C. de la. (2014). The Promise and Perils of Populism: Global Perspectives. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- Wolin, S. S. (2006). Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innovation in Western Political Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press.