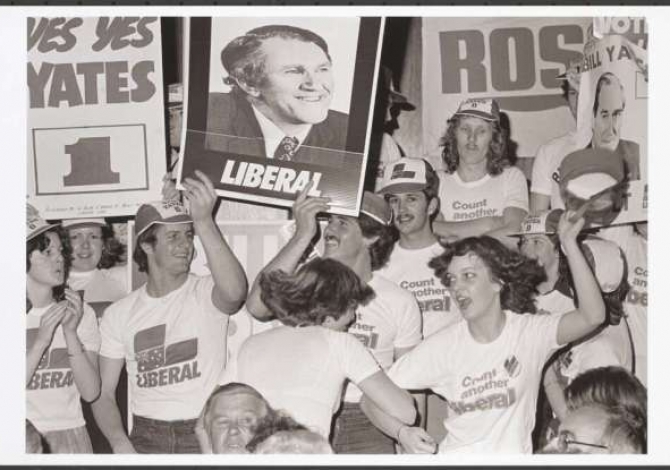

How stable is the Liberal party?

Since the Second World War the Liberal Party has dominated centre-right Federal politics in Australia. However, in the last two years major conflicts have arisen between the liberal and conservative wings of the party. Can it survive in its current form or is some kind of schism inevitable?

Political parties are central to democratic representation. One of their key functions is the aggregation of voter preferences into voting alternatives at elections. A political party with an identifiable ideology or policy program provides a rational voting option for voters whose preferences are consistent with that ideology or program. Historically most voter preferences came within a single left/right dimension that was primarily economic in nature. It reflected the traditional contest between labour and capital. This dichotomy resulted in the electoral dominance for many years of two competing parties – the Australian Labor Party and the Liberal Party (in coalition with its junior Nationals partner). That dominance was reinforced by the electoral rules for the House of Representatives which make it difficult for minor parties to win individual seats and which therefore diminish the value of voting for such parties – the application of Duverger’s Law to the alternative vote/single member district system.

With the advent of post-material issues in the 1960s and 1970s the unidimensionality of Australian Federal politics began to break down. Social, cultural and environmental issues all emerged as political dimensions in their own right. This has made it increasingly difficult for the two major parties to accurately aggregate the preferences of voters. To date the most significant consequence of this development has been the rise of the Greens Party. The inability of the ALP to satisfy the environmental preferences of some centre-left voters without losing the support of the centre-left voters who do not share those same preferences, has caused a fracturing on the left of the political spectrum. No equivalent fracturing has occurred on the right but the prospects of such an event are increasing.

The Liberal Party incorporates two distinct, and not infrequently incompatible, political philosophies – liberalism and conservatism. At its inception, and for many years afterwards, the party was in large part defined by its opposition to socialism, a standpoint equally consistent with both philosophies. To that extent the party could successfully aggregate the preferences of both liberal and conservative voters. However, this common cause disappeared in the 1980s when the ALP embraced neo-liberal economics. Furthermore, by the time that John Howard won government in 1996 the social, cultural and environmental dimensions were throwing up issues that generated ideological disagreements between liberals and conservatives.

While Howard leaned toward conservatism, he was above all a pragmatist. Through a combination of personal popularity and consummate political skills, he held together what he described as the Liberal Party’s ‘broad church’. Ideological differences within the party were soothed by electoral success. The grievances of potentially disgruntled back-benchers were assuaged by the knowledge that Howard represented their best prospects for parliamentary tenure. He skilfully mixed economic liberalism with social and cultural conservatism but without ramming either down anyone’s throat. The strongest resources boom in a century eased his task.

Soon after Howard left the stage the cracks started appearing. The first challenge was climate change, an issue that threatened to tear the Liberal Party apart and ultimately led to Tony Abbott’s victory by one vote in a leadership spill against Malcolm Turnbull. The party subsequently refocused its attention on opposing the ALP. However, the power to make policy since the 2013 election victory has exposed intense ideological conflicts within the party across the different political dimensions – social (gay marriage; euthanasia), environmental (climate change; coal seam gas), cultural (asylum seekers; immigration; Constitutional recognition of indigenous Australians) and economic (foreign ownership of Australian assets; paid parental leave). The dumping of the deeply conservative Abbott as both Liberal Party leader and Prime Minister, and his replacement by the liberal Turnbull, highlight the depth of these conflicts.

The Liberal Party now faces two risks. The first is that it will not be able to contain the disparate political agendas of its parliamentarians and that a major breakaway will occur. Can one party simultaneously satisfy the wishes of arch conservatives like Eric Abetz and Cory Bernadi and liberals like Marise Payne and Turnbull? The second risk is that the Liberal Party will no longer be able to successfully aggregate the policy preferences of both liberal and conservative voters. That could lead to the leakage of support to other parties (including Coalition partner the Nationals and far-right parties like the Australian Liberty Alliance), or, more dangerously, trigger the formation of a new more ideologically consistent party focussed solely on either liberalism or conservatism. The task of holding together the Liberal Party’s broad church has never been more daunting.

This article first appeared on The POP Politics Blog, and can be found here: https://poppoliticsaus.wordpress.com/2016/02/22/how-stable-is-the-liberal-party/