Beware of those who use 'the people' to drive through Brexit

In 1915 influential jurist Albert Venn Dicey defined parliamentary sovereignty as “the right to make or unmake any law whatever”, and whereby “no person or body” would have the right to “override or set aside the legislation of Parliament.” The nature of this legislative sovereignty underwrites Britain’s “unwritten” constitution. However, when the British public voted by 51.9% to leave the EU, influential politicians and pundits claimed that the non-binding referendum result was an expression of the “popular will”. The government, they argued, was bound to legislate on this will.

In the months since the referendum, it has become routine for politicians and pundits to claim that the will of “the people” is paramount, even over parliamentary sovereignty. In the first Conservative Party conference following the referendum, Theresa May commanded her government to “respect what the people told us on the 23rd of June – and take Britain out of the European Union.” When, in November, the High Court of Justice ruled that Parliament had to legislate on Brexit, the Daily Mail accused the judiciary of being “enemies of the people”. The Justice Secretary, Liz Truss, was noticeably slow to defend the judges. Meanwhile, Nigel Farage of UKIP warned that a 100,000 strong “people’s army” would march on the Supreme Court.

But who is morally worthy to count as “the people”? When introducing herself to the public as the new PM, May appealed first and foremost to the “just about managing”. Pouring scorn on the European parliament just days after the referendum, Farage argued that Brexit was the will of the “little people”. Douglas Carswell, UKIP’s first elected MP (now an independent), envisaged his old party becoming heirs to the Chartists and the Levellers, a claim that would make even a Red Tory blush. Or take one pundit’s argument that the deserving “people” who voted Brexit had finally revolted against the undeserving “elites” or “establishment”. For other commentators, Brexit was straight-forwardly a “two fingered salute” from the working class. It is, indeed, the working class who are being invoked as “the people”.

And now Article 50 has been triggered. At this juncture, I am not interested in defending the “sovereign in parliament” from the demands of the working class. Rather, I want to challenge the way in which the “popular will” has been crafted into a weapon with which to drive through fundamental political changes in the most authoritarian manner. Specifically, I want to revisit the referendum vote in order to qualify the following claims made of “the people” by notable politicians and pundits in the last ten months:

- Brexit was delivered by the working class.

- Don’t call the working class racist: this was a vote for sovereignty not a vote against immigrants.

- Brexit was a response to the negative social and economic impact of EU membership.

Brexit was delivered by the working class

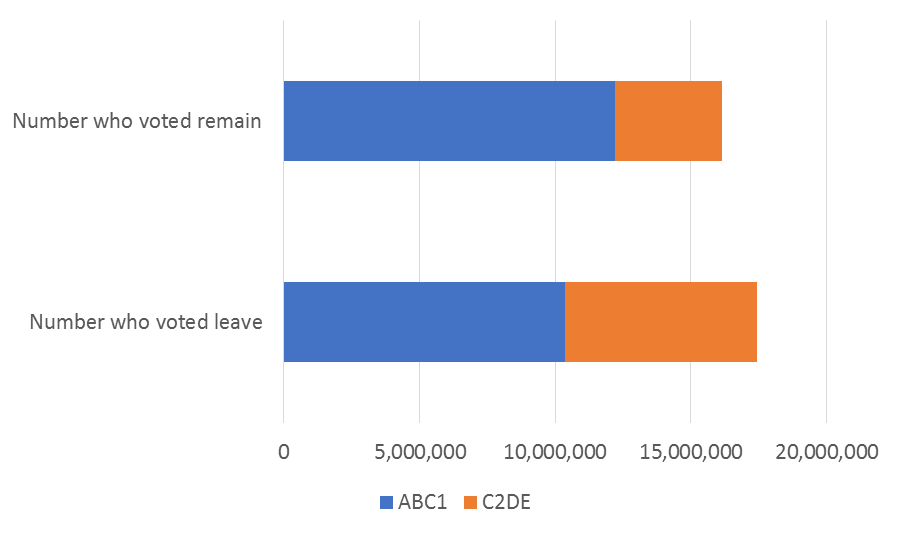

The Ashcroft polls clearly demonstrate that the “lower” the social grade (C2DE) – a standard proxy, albeit problematic, for “working class” - the more likely one was to vote leave. But does this mean that the working class carried the vote? As would be expected, turnout amongst the “upper” social grades (ABC1) remained higher than for C2DE. In fact, roughly 68% of the C2DE population eligible to take part in the referendum did not vote to leave, and this was despite the participation of 2.8 million usually disengaged citizens who overwhelmingly buoyed the leave vote. Ultimately, by calculating projected numbers, it can be safely argued that while the majority of C2DE voters cast a leave vote, the numerical majority of leave voters came from the ABC1 social grades.

Moreover, because of differential turnout, approximately 52% of respondents to the Ashcroft polls who voted leave were from southern constituencies and not from the north (typically considered the heartland of the working class). In fact, the leave vote does not map neatly onto topographies of poverty. At local authority level, indices of deprivation did not strongly correlate with the leave vote. And to this consideration we must add differences within the urban environment. Peripheral, predominantly white housing estates tended to vote leave; inner city areas with significant percentages of Black and minority ethnic peoples tended to vote remain. Of course, the working class are not homogenously white. Black voters overwhelmingly cast a ballot to remain, and Britain’s Black citizens are twice as likely to live in poverty than their white counterparts.

No doubt, class significantly influenced the vote. Yet it did so in complicated ways. In any case, the leave vote was not delivered by the working class.

Don’t call the working class racist: this was a vote for sovereignty not a vote against immigrants

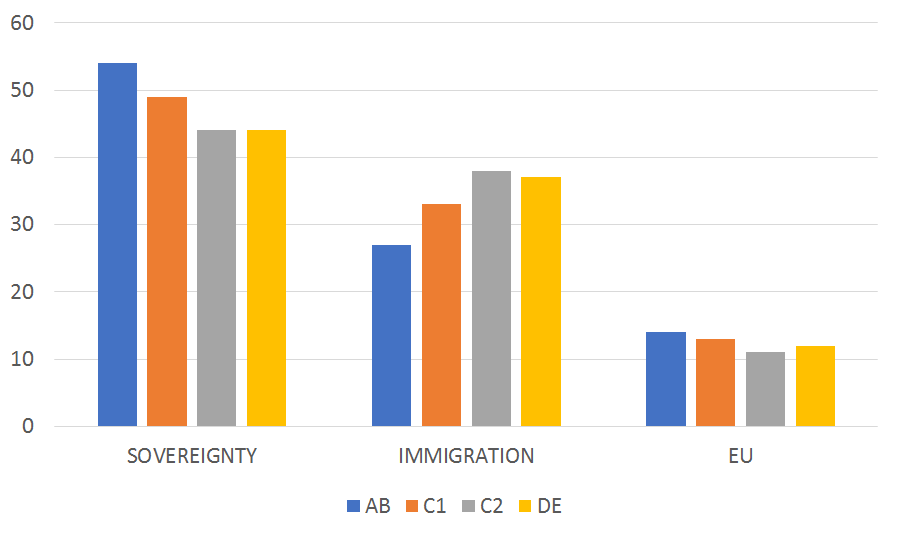

Ashcroft pollsters gave voters a set of pre-articulated claims to rank in order of importance. Leave voters clearly ranked two claims above others: “the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK", and “voting to leave offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders”. While the abstract issue of sovereignty prevailed as the first choice amongst all social grades of leave voters, the more concrete issue of immigration came a close second.

Other surveys provide similar findings. A NatCen survey undertaken just after the referendum found that 88% of those who identified immigration as the most important issue voted leave, as did 90% who identified sovereignty. Additionally, a Yougov survey in August 2016 identified immigration to be the biggest issue that differentiated leave from remain voters.

Of those who voted leave, the Ashcroft polls show that relatively more ABC1 voters identified sovereignty as of prime importance than C2DE voters, and that the preference for sovereignty over immigration was far more attenuated amongst C2DE voters than was the case for ABC1. Additionally, when all respondents were asked whether immigration was a force for ill, a (sizeable) minority of AB (32%) and C1 (39%) voters agreed, compared to a slim majority of C2 (51%) DE (53%) who agreed. It seems, then, that C2DE leave voters were more anti-immigration than their ABC1 counterparts.

But let us take care here. In the weeks leading up to the referendum, the leave campaign took extraordinary measures to link the abstract principle of sovereignty with a concrete concern for immigration. Furthermore, an ethnographic study suggests that people belonging to higher social grades tend to articulate moral argument over race and nationality in far more abstract language than those from lower social grades. These considerations might explain the different weightings between ABC1 and C2DE leave voters when it came to identifying sovereignty and/or immigration as key rationales.

We can also approach anti-immigration sentiment along vectors other than class. Here, I want to invoke the historically racialized coordinates of English nationalism, which cut across class. Indeed, the Ashcroft polls suggest that the more a voter identified themselves as English the more (68%) they would see immigration as a force for ill in distinction to voters who identified themselves with British (30%).

In light of a rise in racist hate crimes following the June referendum, the question of working-class racism has come to the fore. During the campaign and in its aftermath some commentators sought to sanctify the working class as a constituency who simply wanted to throw off the patronising shackles of a metropolitan establishment. Others, though, have been more thoughtful and careful in their analysis of racism. I would suggest that immigration was the key concern that distinguished the leave from the remain vote. However, anti-immigration sentiment was in no way confined to the working class and emanated in good part from English nationalism.

Brexit was a negative response to the social and economic impact of EU membership

As can be seen from the graph above, Ashcroft found that concern over the expansion of EU membership and powers polled a distant third in terms of reasons for voting leave. Alternatively, leave voters were much more likely to have a negative outlook on their standard of living and their children’s prospects than remain voters. So, what does the evidence say of leave voters’ apprehensions of socio-economic issues?

The Ashcroft polls suggest that those issues considered most relevant to the vote – i.e. quality of life, opportunities for children, economic security, the economy as a whole, and job prospects - were less likely to be those issues that polarised voters vis-à-vis EU membership - i.e. ability to control laws, the immigration system and border controls. In fact, negative changes in earnings over the last 15 years (an era coinciding with increased EU migration) did not strongly correlate to a vote to leave, but entrenched geographical differences in earnings correlated far more. Indeed, the leave vote was more predominant in areas of decline which happened to be old manufacturing centres. It is true that the white vote to leave was stronger in those areas that had seen a recent and relative (but not absolute) increase in “outsiders”. Nonetheless, an Ipsos-Mori poll conducted 10 days before the referendum revealed that only 39% of potential leave voters believed European immigration had negatively impacted upon the area where they lived, and only 36% believed that such immigration had personally impacted them in a negative fashion.

I am suggesting, then, that those who voted leave did not do so in direct response to the impact of EU membership upon pressing socio-economic concerns. These concerns emanated from much closer to home.

There remains, though, a puzzle. When the same Ipso-Mori poll asked about the national impact of such migration, 65% of leave voters concurred that it had been negative. To address this discrepancy between the local and national we need to consider how the impact of long-term neoliberal transformations on welfare and public services have been apprehended, especially by poorer communities. In his studies of “whiteness”, Steve Garner notes that entitlements to welfare are often perceived to have their basis in national belonging rather than in local contexts. In a forthcoming book, Colonial Genealogies of the Deserving Poor: From Abolition to Brexit, I argue that this nationalisation of entitlement sentiment is linked to the historic dissolution, via the 1948 National Assistance Act, of the formal distinction between the deserving and underserving poor. I also argue that at the same time this distinction was informally racialized so as to place the homogenised deserving “white working class” in opposition to undeserving “immigrants” from the “new” (i.e. majority coloured) Commonwealth countries.

This is the immediate context in which English nationalism was racialized as white, as were sentiments to welfare entitlement. However, with the onset of “workfare” policies under New Labour, the deserving/undeserving distinction was re-introduced into the white working class itself, which produced, for the first time, an uncomfortable social residue – the distinctly “white” underclass. Nonetheless, being white, this underclass presently still retains membership of the English family and hence, while bemoaned, is considered deserving of salvation, unlike “migrant” communities (including east Europeans). Interestingly, the Ashcroft polls confirm that a comfortable majority of voters in each of the B, C1, C2, D and E status groups believed fairness in the welfare system would improve if the UK were to leave the EU. And even 49% of the A group agreed.

For all these reasons, I would argue that the leave vote was influenced much less by recent changes in economy and society engendered by EU membership/enlargement and much more by abiding disparities and divisions caused by postcolonial population shifts, de-industrialization and the neo-liberal transformation of public services.

The leave vote was not delivered by the working class (capital W, capital C). Immigration was the key issue that differentiated the leave vote from the remain vote. However, anti-immigration sentiment was in no way confined to the working classes and should perhaps be considered a general symptom of English nationalism. Furthermore, the concern that leave voters expressed over socio-economic issues was less a response to the effects of EU membership/enlargement and much more embedded within long-term disparities and divisions that currently structure postcolonial, post-industrial, neoliberal Britain.

These are crucial qualifications to the claims presently being made of “the people” in pursuit of Brexit. And I want to give these qualifications extra critical force by linking them to commentaries recently provided by Gurminder Bhambra and John Holmwood. Both argue that the historical framework for addressing Brexit must reference British empire and not simply the European project. I believe that this reorientation is crucial to adequately understand the weaponizing of the “white working class” into the constituency that supposedly represents the “popular will” for Brexit.

The parliament of Great Britain was formed in 1707 by the union of England and Scotland, two polities that possessed colonies and colonial ambitions. In the succeeding centuries, parliament governed over not just a national economy but a vast imperial hinterland of land, labour, raw materials, markets and influence. Later this hinterland became a Commonwealth that effectively saved the Sterling economy in the reconstruction period immediately post World War Two. Pre-empting the effective loss of this hinterland, Ted Heath finally engineered the successful accession of the British economy to the EEC in 1973. The EU has since functioned for the British economy as a kind of substitute to the hinterlands of empire. There is, then, a terrible irony to Theresa May’s optimistic invocation of a post-EU “Global Britain”. In fact, for the first time ever, parliament will have to govern over and reckon with a truly national economy. (And one, perhaps, even shorn of Scotland).

What work is the authoritarian dictate of the “popular will” doing at this unprecedented juncture in the history of parliamentary democracy?

One could say that at one point in the 20th century racism and xenophobia served to elevate at least some of the “white” working classes into a position of security that they had previously not enjoyed. This is patently not the case today. It is not the case even while it is Black and minority ethnic peoples who are over-represented in suffering the negative effects of austerity policies. “The people” are presently being weaponised through racist and xenophobic sentiment into a constituency through which a new era of brazen capital accumulation is being inaugurated. This is an era wherein the living – and not imagined - working classes will have no recourse to a hinterland of social security. Perhaps Britain is finally receiving its comeuppance for past crimes. But let us not forget that, in the recent history of neoliberalism, Britain has tended to chart a course where others have been only too keen to follow.