Is There Such a Thing as Asian Culture?

In their recently published paper in the Asian American Journal of Psychology, sociologists Min Zhou and Jennifer Lee examine the reasons behind the extraordinary socioeconomic achievement of Asian Americans. Asian Americans exhibit the highest median household income and highest level of education of all U.S. racial groups, even surpassing native-born White Americans. At 5.5 percent of the U.S. population, Asian Americans are highly visible in Ivy League universities and prestigious public universities, where they account for 20 to 40 percent of the student body. Pundits, journalists, and some scholars have attributed their socioeconomic achievement to cultural values or traits—such as the emphasis on hard work, career development, marriage, parenthood, and family cohesion—that they characterize as innately Asian. This “culture of success” thesis is merely the antithesis of the popular and highly contested “culture of poverty” argument.

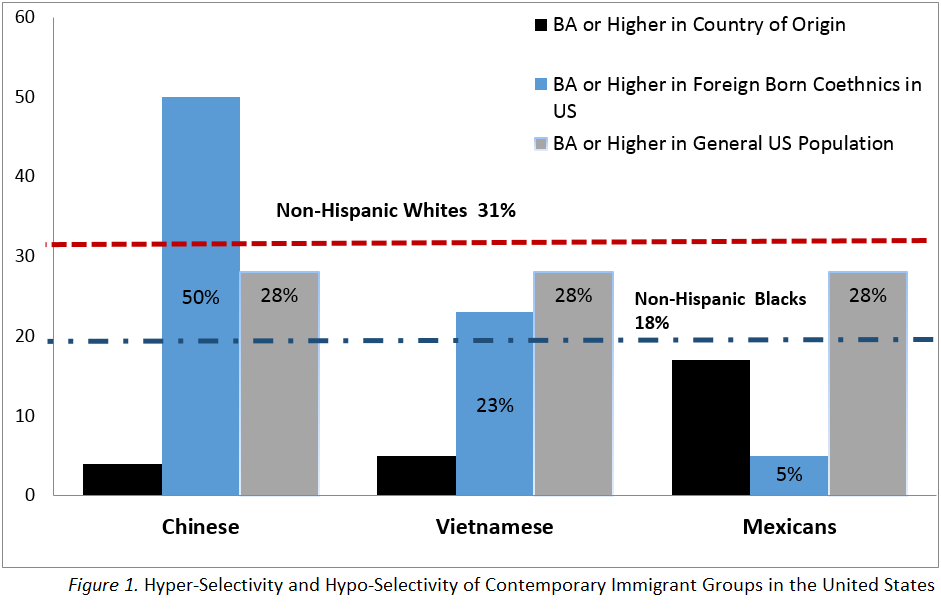

Zhou and Lee challenge the culture of success antithesis head on. They argue that there is no such as a thing as Asian culture. Rather, culture has structural roots. What seem to be common cultural patterns among Asian Americans emerge from the structural circumstances of contemporary immigration. The prevailing cultural explanation fails to consider the pivotal role of U.S. immigration law, which ushered in a new stream of highly-educated, highly-skilled Asian immigrants. The authors call this unique circumstance “hyper-selectivity,” defined as an immigrant group arriving in the U.S. with a significantly higher percentage of college graduates than that of the adult populations in both receiving and sending countries. The opposite is “hypo-selectivity,” referring to an immigrant group arriving in the U.S. with a significantly lower percentage of college graduates than that of the adult populations in both sending and receiving countries. Hyper-selectivity has profound consequences for the socioeconomic attainment of not only immigrants but also their children.

The authors examine several critical consequences of hyper-selectivity that affect Asian Americans’ socioeconomic achievement: starting points; success frame; ethnic capital; and stereotype promise. Their analysis is based on a qualitative study of adult children of Chinese, Vietnamese, and Mexican immigrants in metropolitan Los Angeles. Chinese are the largest Asian ethnic group in the United States and Los Angeles. They are also among the most hyper-selected of Asian immigrant groups. Vietnamese are the largest Asian refugee group in the United States. Although they arrived with severe structural disadvantages, the Vietnamese are nonetheless highly selected, rather than hyper-selected. Mexicans are the largest immigrant group in the country (accounting for 30 percent of U.S. immigrants) and also the largest immigrant group in Los Angeles. Their sheer size—combined with their disadvantaged status as a hypo-selected group—often puts them in the spotlight of policy debates about immigration and comprehensive immigration reform.

The authors find that the hyper-selectivity of contemporary immigration positively influences the educational trajectories and outcomes of the children of immigrants beyond individual family or parental socioeconomic characteristics, resulting in group-based advantages. In particular, the children of Chinese immigrants begin their quest to get ahead from more favorable starting points, are guided by a more constricting success frame, and have greater access to ethnic capital to support the success frame than those of other immigrant groups such as Mexicans. In turn, these group-based advantages help the children of Chinese immigrants, including those from working class families, excel in school. The desirable educational outcomes produce stereotype promise— the boost in performance that comes with being favorably perceived and treated as smart, high-achieving, hard-working, and deserving—that benefits not only the hyper-selected group members, like the Chinese, but also other group members who may not be hyper-selected but are racialized as Asian, such as the Vietnamese.

Zhou and Lee conclude that Asian culture is not innate, but is remade from selective Asian immigration. Children of highly educated immigrants begin their quest to get ahead from more favorable starting points, have greater access to ethnic capital to support a success frame, and benefit from positive societal perceptions and stereotypes. The authors caution that, while the so-called positive stereotypes enhance the academic performance of Asian American students, the same stereotypes hinder them as they pursue leadership positions in the workplace. Asian American professionals face a bamboo ceiling—an invisible barrier that impedes their upward mobility much like the glass ceiling does for women—pointing to an Asian American achievement paradox.

Citation:

Zhou, M., & Lee, J. (2017). Hyper-selectivity and the remaking of culture: Understanding the Asian American achievement paradox. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 8(1), 7-15.