From Antagonistic to Agonistic Memory: Should the Statues Fall?

The notion that our view of the past shapes our sense of who we are our today, both individually and collectively, has long been recognized, and politicians have equally long been aware that shaping the narrative about national history can have distinct political advantages. Whoever can dominate that narrative can also, in theory, influence the collective values of a society.

In practice, however, competing political forces tend to propose competing visions of the national story. These can be the starting-point for emotionally charged and even violent conflict. How do societies cope with such tensions?

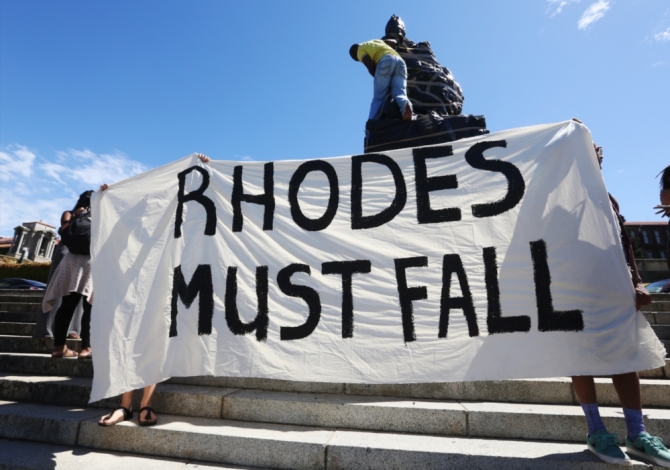

Recent controversies in South Africa and the US over the material heritage of colonialism and slavery show some of the dangers of such conflicts over history. Both involve the removal of statues and other material traces honouring colonialists such as Cecil Rhodes and slave-owners such as Confederate President Jefferson Davies, which protesters claim help to perpetuate the injustices of the past.

The removal of statues following regime change, whether after the end of World War Two or following the fall of Communism in eastern and central Europe, can, of course, be a matter of common consent. Such iconoclasm can be a way for a society to demonstrate its commitment to a new set of values and a new way of living together, freed from the legacy of the past.

The controversial ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ protests in South Africa in 2015 and 2016, which did lead to the removal of the offending statue of the British colonialist, may in the long term prove to be a productive moment for that society’s dealing with its past: by attacking the statues, the young students involved in the protests were pointing to unresolved legacies of colonialism in the everyday lives of their communities and called on the political establishment to recognise how much still needs to be done to overcome those legacies.

However, when the protests spilled over to the University of Oxford in the UK, where Rhodes is also honoured, they were widely criticised in the mainstream media and politics as another example of ‘political correctness gone mad’ and a threat to the British past as a whole: after all, it was argued, where would it end? Would we have to get rid of statues of Cromwell and other British heroes whose record is far from unblemished from today’s perspective?

Yet another case is provided by Italy, where busts and paintings of Mussolini survive unscathed to this day as they are considered artistic objects or reminders of the country’s history. Yet, disturbingly, many architectural sites or monuments are not historicised and visitors may well come away with an uncritical if not outright positive view of the regime. In 2012, a local protest by students and citizens in Ascoli Piceno resulted in a painting portraying Mussolini as a Roman warrior on horseback being removed from a secondary school, but these episodes tend to be rare.

How can we deal with these conflicts productively? The first thing to say is that, as the examples above show, we are looking at diverse cultural contexts. While there may be a certain contagion of forms of protest from one country to another, the nature of what is at stake in each case needs to be carefully understood.

Nevertheless, what is clear is that removing or erasing the traces of the objectionable past, whatever the justice of individual cases, seeks to replace the old understanding of history with a new one, leaving no room for a plurality of points of view. In our current work as part of the EU-funded research project ‘Unsettling Remembrance and Social Cohesion in Transnational Europe (UNREST)’, we are developing new theoretical approaches to issues of this kind. We would call the desire to remove statues and other monuments as an ‘antagonistic’ form of memory activism that is likely to produce strong counter-reactions and a sense of threat of the kind we currently see in confrontations over Confederate statues in New Orleans. Such antagonism closes the possibility of dialogue.

An alternative would be an ‘agonistic’ approach to the material traces of history in public spaces. By leaving those traces in place, but at the same time re-contextualising them through the addition of other information or artistic interventions, it might be possible to acknowledge both the conflicts of the past and the differing and even contrasting views of this troubling past that continue to exist in the present. In this way, the celebratory, glorifying or nostalgic narrative styles that characterise such traces of the past become problematised while perpetratorship can be both exposed and critically reflected upon.

In addition, leaving monuments and statues in place even long after the attitudes they represent have ceased to belong to the mainstream is potentially a reminder to society as a whole of how and why it came to think or behave in certain ways. Removing the material heritage of the unsettling past prevents us (or the communities we identify with) from reflecting on our own dark heritage and understanding the historical contexts in which socio-political oppression and even mass crimes became possible.