UK International Development Policy post Brexit?

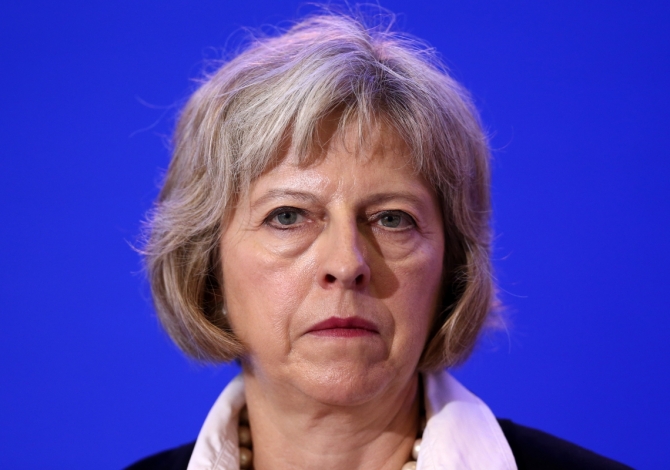

Theresa May’s announcement that the "0.7% commitment remains and will remain” has appeared to head off the likelihood that a future Conservative government will repeal the 2015 International Development Act in the next Parliament. This is the Act that legally requires the UK to spend 0.7% of its GNI on Official Development Assistance. Her statement ended speculation that the target was at risk. In his Autumn Statement the Chancellor Phillip Hammond had said that ‘We will keep our promise to the world’s poorest through our overseas aid budget …. But as we look ahead to the next Parliament, we will need to ensure we tackle the challenges of rising longevity and fiscal sustainability. And so the government will review public spending priorities and other commitments for the next Parliament in light of the evolving fiscal position at the next Spending Review’.

This appears to suggest that the law could be re-examined.

May’s statement has been interpreted by some as a brave move given that the 0.7% commitment, and the decision to ring fence the spending from austerity, is very unpopular within certain sections of the Conservative Party and the British media. Aid spending is an interesting element of government spending as it is money spent ‘beyond the water’s edge’. The Brexit decision emboldened these critics of UK aid, who believe they have the support of a majority of the British people to cut the aid budget, with this majority being made up of a similar demographic to those who voted Brexit. Indeed the Scottish Conservative leader, Ruth Davidson, said that commitment to the target requires ‘moral courage’. In the current election campaign, we see aid pledges being used as counterpoint to spending pledges made by the political parties. For example, the plan by the Liberal Democrats to raise income tax by 1p to pay for the NHS was contrasted by journalists to their commitment to the 0.7% target, with the implication being cut aid to keep taxes low.

However, the focus on the amount does not tell the whole story. The Prime Minister highlighted that ‘what we need to do, though, is to look at how that money will be spent and make sure that we are able to spend that money in the most effective way’. As DfID is one of the most transparent government departments we are able to get a good insight into how government priorities influence its work.

The 2015 Treasury Policy Paper “UK aid: tackling global challenges in the national interest” highlights the importance of national interest in aid spending.

Part of the national interest narrative is reflected in shifts in the ODA in the budget away from DfID to other departments, with a quarter of the aid budget (£3.5 billion) being spent outside DfID in 2016. We also see increased use of cross-government funds, such as the Prosperity Fund and Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF). Consequently we can identify an increased focus on security and the private sector, a trend identified by Stephen Brown as the ‘commercialisation of aid’.

While poverty reduction programmes and goals certainly remain important, much of the new energy and investment of the Conservative aid strategy has been in stimulating trade and private sector-led development. In a recent paper, we argued that there is a clear narrative that Brexit will accelerate the trend to utilise aid to secure trade deals, given the need for the UK to re-focus its foreign and trade policy away from the EU.

There is also an option to increase the volume of aid devoted to business investment. This would fit with the proposal from DfID to increase the support the government can give to CDC, the UK development finance institution from £1.5bn to £6bn.

Given the amount of pressure the government faces to maintain 0.7 percent GNI aid spending, some changes in how that aid is used are inevitable. The focus on fragile states in the DfID strategy inevitably links development and security more closely. However, that does not mean security should replace poverty reduction as the focus of UK aid nor should aid include military spending. The changing nature of aid modalities towards technical assistance may mean that the private sector is best placed to provide the knowledge.

However, that should not mean the private sector is always the best partner. Supporting refugees is important but diverting aid to fund the cost of hosting these refugees or reclassifying these costs as aid will weaken UK aid.

The recent Conservative Manifesto reinforces the view that what the UK classes as aid is likely to change if, as most polls predict, Theresa May’s party win the 8 June election. It states that whilst they will maintain the 0.7% commitment, they will work with like-minded countries to change the aid rules. The next line is telling; ‘If that does not work, we will change the law to allow us to use a better definition of development spending, while continuing to meet our 0.7 per cent target’.

Brexit puts increased focus on the UK’s ability to promote its soft power globally and DfID has considerable experience in the area. DfID is a well-respected government department both within the UK and internationally. DfID should therefore not be restricted in carrying out its core work, to reduce poverty, by growing pressure to act in the UK’s national interest. Clearly an aid policy which is supported by the British people and works for the UK is politically expedient but the UK has a proud record on aid and it is vital that nothing should negatively impact upon this record at this crucial time in British foreign policy.