What's Left of the Left?

The paradox of the contemporary European left is that while many of the burning issues defining political debates – growing economic inequality, employment precariousness, the sustainability of health spending or pension entitlements – are traditional left-wing concerns, social democratic parties are incapable of credibly addressing them either in office or in opposition. The standing Socialist head of state – Francois Hollande – was not a candidate at this year’s French Presidential elections after registering levels of popularity even lower than Jeremy Corbyn in the UK.

So, what’s left of the left? The origins of the paradox stems, in part, from the mis-match in the architecture of authority, in Europe and elsewhere, between democracy and capitalism, rendering the notion of democratic capitalism ever more hollow.

Social democracy is organised, as any kind of democracy, at the level of the nation-state. The levers of public intervention in matters of risk insurance (employment, health, pensions), remain with national governments. Market forces on the other hand operate at the regional or global scale. The European Union does intervene in regulating trans-national market competition by, for example, applying Europe-wide directives protecting employees. But, membership of the Eurozone also curtails national government’s room for manoeuvre in how much they can spend and borrow. And the EU has not acquired the kind of legitimacy so long bestowed on elected national governments. At an extreme, the EU stands in direct opposition to the wishes of democratically elected governments – as Syriza voters in Greece know only too well.

This tension has compounded broader demographic and economic transformations to divide the electoral base of the left. In France, the UK, the USA and elsewhere, there is a split between those in favour of regulated openness and those in favour of nationalist closure. In that choice, there is a troubling echo of the choice that the working and middle classes confronted during the inter-war crisis period between socialism, nationalism, and liberal democracy. And the parallel between now and then is reinforced if one considers that identity has taken centre-piece in the current debate, as foreign creeds, especially Islam, become broadly designated as the new enemy from within and without.

These divisions are well known: the old industrial working-class, typically white and male and living in the traditional strongholds of the Labour Party or Parti Socialiste – areas like Barnsley or Middlesbrough, Lille or Amiens – have turned towards UKIP and the Front National who offer quick solutions that restore national control over borders and the economy. The other segment in the left’s electoral base, public sector employees, liberal professionals, urban residents with a cosmopolitan outlook, remain in favour of the current disposition, and continue to espouse socially liberal ideals and economically centrist policies.

This fragmentation on the left was perfectly illustrated in the first round of the French presidential elections: Hammon, the candidate for the established Parti Socialiste, lost votes to the far left (Melenchon), to the centre (Macron) and to the far-right (Le Pen), all of which took around one-fifth of the vote. In the second round, Macron retained the votes of centrists on right and left, while some of Melenchon’s supporters drifted to Marine Le Pen. The Labour party’s electoral base faces a similar threat of disintegration to working class English nationalism in the Conservative party, Scottish nationalists (SNP), and the Liberal Democrats. In Spain, the PSOE has lost support to Podemos on the left and to the centrist upstart, Ciudadanos.

So how have centre-left parties responded to this predicament?

There appears to have been something of a revival in left-wing parties that augur if not a resurgence of socialism, then at least a rejection of nationalism, that might help to counter this fragmentation.

Corbyn’s dramatic election as leader of the Labour Party in 2015 was made possible by a sudden growth in the number of young and committed party members. Macron’s equally impressive victory in the French presidential election seemed to signal a similar popular momentum. Matteo Renzi took the helm of the Partito Democratico in Italy, committed to tackling the country’s deep structural problems, on the back of an immense surge of popularity. In Spain, Podemos has built upon the bases of the 15-M social movement, to protest against economic austerity, corruption, and collusion between the established political parties.

But unlike the emergence of the ‘New’ Left in the late 1990s, incarnated in the UK (Blair), Germany (Schroder) and France (Jospin), these movements do not share the common ideological vision or political organization that is required to make them successful in winning office and implementing their programmes.

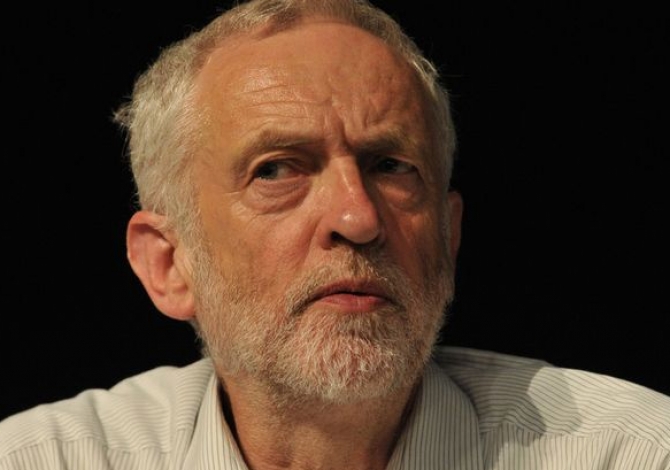

Corbyn’s problem is that he is unlikely to win office. He is a well-known but unpopular tribune speaker with rehearsed socialist ideas, such as state ownership of railways, that will not pass muster with the average British elector. But, he is in the desirable position of leading a powerful ground-level organization with a large membership and deep organizational roots.

Macron is the opposite of Corbyn: a capable and well-liked political novice, with a pragmatic but nevertheless reformist programme that can woo centrist voters on left and right. But, his problem is that he will have difficulties implementing his programme. Like, Pablo Iglesias, the leader of Podemos, he leads a loose movement (En Marche!) rather than an established party. And it is not clear if this movement will be organized and cohesive enough to field candidates in the forthcoming legislative elections, the results of which will determine the composition of the government with which the President of the Republic must work.

Renzi’s problem is also one of implementation. At first, he seemed to have the best of both worlds. He was bright and dynamic young leader with a positive record of achievements as Mayor of Florence, at the helm of a dominant ruling left-wing party, that wished to solve Italy’s deep-seated economic problems and to tackle vested interests. However, Renzi fell victim to hubris and lost his gambit to reform the Italian political system, where the diffusion of power across institutions threatened the implementation of his ambitious programme of reform.

Given this record of false dawns, what is needed for a successful revival of the centre-left?

The conditions for success appear to be those that combine the best of protest, personality, policy, and party organization: one in which Macron’s reforms could draw upon the groundswell of support offered to Iglesias, the organizational depth of Corbyn’s party and the systemic dominance of Renzi’s party. Following from this, there are five main guidelines that social democratic parties can adhere to if they wish to be successful:

- The recipe for success must begin with an emphatic revival of the importance of social justice issues like long-term unemployment, education and training, health funding or pension reform, which have always been at the heart of social democracy, relative to other issues like immigration and identity, which tend to pull voters into the orbit of far-right parties.

- Left-wing parties must put forward novel and concrete policy proposals that credibly deal with social justice issues, but that also recognize the complexity and constraint of living in an open world, rather than offer an unrealistic return to a fictitious golden age of closure. Taking inspiration from Macron and Renzi’s programmes, that means reforming pensions, liberalizing a sclerotic labour market, using state instruments to prevent the worst forms of deprivation and to use public funds to provide social investments – in health, education and training and industrial relations – that will boost the supply side of the economy.

- The success of this strategy also depends on the ability of left-wing parties to mobilize the younger generation of voters to whom such a message might appeal. The split within the left is partly a generational one, and the younger generation are a more rewarding current and future electoral bank, and more sympathetic to reformist ideas. So, they must be compelled to vote. This will require the transformation of loose movements into formal party organizations with resources, personnel, and members.

- Given the split of the leftist electorate and the fragmentation of the political landscape, centrist and left-wing parties, like their predecessors in the early 20th century, also need to accept to govern in coalition with other like-minded forces. For instance, the only alternative to the Conservative government in the UK is a coalition of Labour, Lib Dems and the SNP. Similarly, in France, Macron will likely require the legislative support of both Socialist and Republican deputies to implement his programme. Failure to coalesce may result in the failure to win office, as Pedro Sanchez, the fallen leader of the PSOE realised only too late.

- Finally, left-wing parties also need to find ways to pursue their programmes at different scales of democracy. They can begin by testing their policy ideas and buttress their electoral support by winning in local or regional government. But, they can also develop trans-national coalitions between similar social segments across different countries, for instance in the European Parliament.

Only by broadening their thought and action in such a fashion can struggling social democratic parties recover their relevance in the current political landscape.