The Media, Euroscepticism and the Debate about Europe

The media play an important role in democratic societies. This also applies to the European Union (EU). In times of increased criticism on the EU it is surprising to see that there has been relatively little dedicated research into media coverage and Euroscepticism. Patrick Bijsmans argues that there is a need to bridge the gap between research into media coverage of EU affairs and research on Euroscepticism.

Because the media constitute important platforms for public deliberation, there has been lots of scholarly attention for various aspects of media coverage – or the lack thereof – of EU affairs. Despite some exceptions – such as Christian Nitoiu’s study on transnational media reporting of EU climate change policy – most research focusses on both the extent and the content of EU affairs reporting by national media, which are widely believe to remain the central platforms for the so-called European public sphere. Studies have looked at several policy fields, events and Member States, as well as at EU communication policies and journalists’ approaches towards the EU.

While coverage varies depending on types of media, Member States and policy areas, media attention for EU affairs generally has been on the increase. However, scholars have questioned the quality of that coverage, pointing at, for instance, the misrepresentation of EU policy-making and the limited attention for policy-making before actual decisions have been taken. Arguably, this complicates attempts to hold the EU accountable. Scholars such as Cécile Leconte have even argued that the misrepresentation of European affairs in national media is an important source of Euroscepticism.

Euroscepticism has increasingly become a mainstream phenomenon that has been studied from many perspectives. Commonly understood as opposition towards the EU and European integration, research has particularly focussed on party politics and public opinion. Surprisingly, there is only little research that combines perspectives of media coverage of EU affairs and Euroscepticism – for an exception see Manuela Caiani and Simona Guerra’s recently published volume. Yet, as has been argued by, for instance, Simon Usherwood and Nick Startin, there is a need to expand the scope of Euroscepticism research to other areas, including the media.

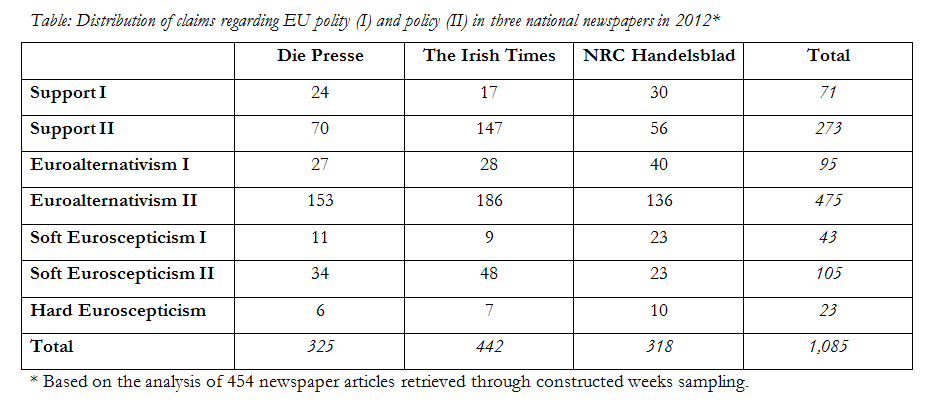

I have been working on research that aims to bridge the gap between the focus on media coverage of EU affairs and on Euroscepticism, with studies that look at both day-to-day coverage of EU affairs and media attention for specific events. Following existing academic work on the conceptualisation of Euroscepticism I have designed a framework that distinguishes between four positions on EU affairs: support for the EU; pro-EU calls for alternative approaches (Euroalternativism); soft Eurosceptic arguments for less EU; and hard Eurosceptic arguments for a complete withdrawal from the EU. For the first three I also distinguish between positions that concern polity (EU treaties, institutions, membership) and those that concern policy (for instance, whether to adhere to strict austerity policies or opt for increased spending during the Eurozone crisis).

Applying this framework to coverage by popular and quality newspapers results in a number of findings. First, media reporting displays a diversity of opinions, often concerning policies rather than polity, and generally arguing for alternative policy approaches rather than arguing against EU involvement. This is something that I found for the media in several European countries, including Austria, Ireland, the Netherlands, and even the United Kingdom. This raises questions about the popular argument that Euroscepticism is on the increase. Instead, while certain aspects of the EU and its policies are criticised and alternatives are being put forward, integration as such does not appear to consistently questioned (see, for instance, the table below from a forthcoming study).

Second, at times of high-profile events the focus does shift towards a pro-con integration debate. The focus of coverage of, for instance, European elections is aimed at integration as such, even though these elections offer an opportunity to discuss the kind of policies that the EU should pursue. The intensity of related debates differs between countries, with, for instance, Euroscepticism having become more ingrained in the Dutch debate since the 2005 referendum on the Constitutional Treaty. Interestingly, in a paper that we have just submitted to a journal, Charlotte Galpin, Benjamin Leruth and I find an increasingly positive account of European integration by Dutch, French and German newspapers at the time of the Brexit referendum in the UK.

Third, and maybe most important, newspaper coverage shows that Euroscepticism has become a catch-all term, with reporting often being quite imprecise. For instance, parties that are critical of certain policies, but not of integration as such, are equalled to those that argue for a rejection of the EU. In fact, ‘Euroscepticism’, and derived words, are widely used both in and outside academia, yet their use is often imprecise. ‘Euroscepticism’ has become a ‘plastic notion’ and an ‘overly reductive term’. Or, as Robert Harmsen wrote, the use of the term Euroscepticism has ‘blurred the distinction between genuine oppositions to European integration and that which might more reasonably be regarded as a normal (and desirable) politicization of European issues within the framework of a multi-level polity.’

In sum, public discourse is often shaped in media debates and these debates appear to display a richer variety of positions towards the EU and its policies than tends to be suggested, suggesting a gradual normalisation of EU debates. At a time in which anti-European movements have become more vocal – and, simultaneously, pro-European voices are increasingly contributing to national debates – there is a need for further research into Euroscepticism and the media, taking into account this broader spectrum of opinions. Only by doing so will we be able to show how the media may contribute to people’s views and stances towards European integration.