Integrating the Next Generation: How School Composition Affects Inter-Ethnic Attitudes

Drawing on new research, Simon Burgess and Lucinda Platt argue that greater mixing of pupils from different ethnicities would be beneficial for social integration.

Social cohesion is high on the political agenda. Understanding how to foster social integration is central to the recently-published Integrated Communities Strategy Green Paper and to the Mayor of London’s Social Integration Strategy. A particular interest is the experience of young people. Tomorrow’s citizens are today’s schoolchildren and time in school has the potential to shape attitudes towards others. In our recent report we estimate the relationship between school ethnic segregation and inter-ethnic relations. To our knowledge, this is the first national study of schools throughout England to relate inter-ethnic attitudes to school and local authority ethnic composition.

While we might all hope that greater mixing of pupils from different ethnicities would be beneficial for social integration, this is by no means certain. Researchers have distinguished between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ contact: only the former improves relations between groups. For example, one of the most celebrated contemporary social scientists, Robert Putnam of Harvard, showed that more diverse neighbourhoods in the US were associated with a breakdown of trust and cohesion.

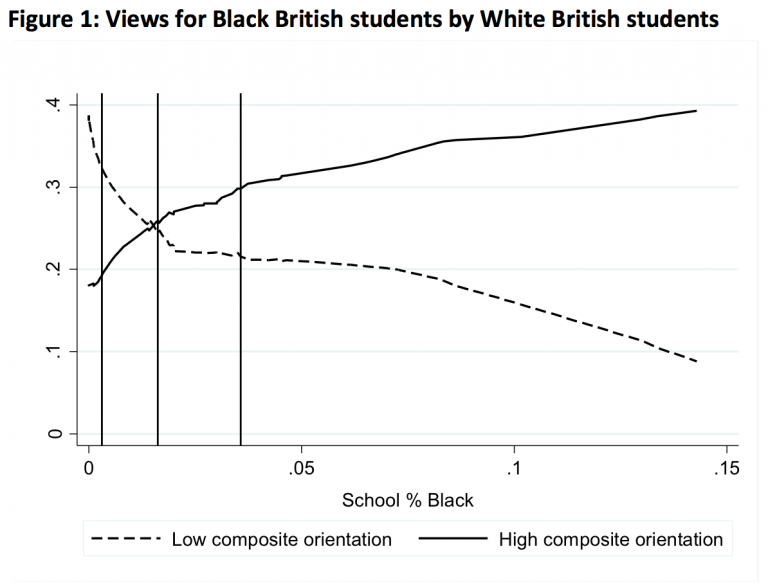

Our findings are clear: pupils from one ethnic group feel more positive towards another group if they encounter more pupils from that group in their school. For example, the ‘warmth’ of feeling of a Black pupil for White British pupils increases significantly and sizeably the higher the share of White pupils in her school; and reciprocally, the warmth of a White pupil for Blacks increases as the share of Black pupils in her school increases. We also develop a rich composite indicator of pupils’ orientation to other groups. This combines the warmth of feeling towards the other group, the number of friends from the other group, and views on multiculturalism. We find the same: pupils are much more likely to have a positive orientation toward another group in schools in which that group is more numerous, and much less likely to have a negative orientation. We can illustrate this in Figure 1:

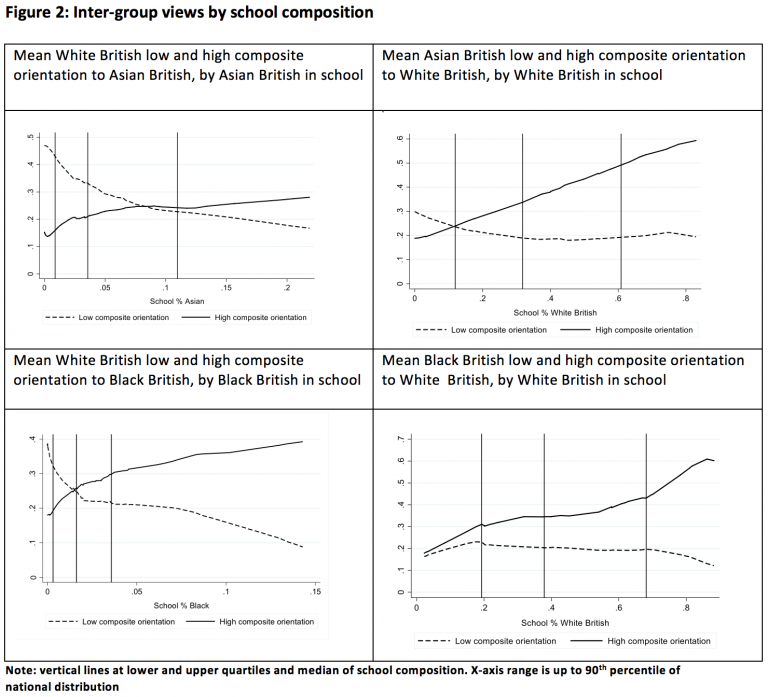

As a White student encounters more Black students in her school, she is more likely to have a positive view of Black British, and less likely to have a negative view. These are sizeable effects and are true of all the inter-group views:

Consider a hypothetical city with 20% Asian and 80% White pupils. A fully segregated system would imply that Asian students experience 0% White pupils and White pupils experience 0% Asian students. Our results suggest that that situation would yield the result that approximately 47% of Whites would have a low orientation towards Asian pupils and around 30% of Asians would have a reciprocal low orientation; so overall 44% of all pupils in the city would be ill-disposed to the other group. By contrast, in a fully integrated system, overall around 20% of pupils would have low orientations. This halving of the number of pupils with such views in an integrated school system seems very valuable. In terms of high orientation, if this city’s schools were fully segregated, only 18% would have high orientations to the other ethnic group, compared to 53% if fully integrated.

These effects endorse the role of schools in developing positive contact through mixing – suggesting that most of what happens in schools is ‘good contact’. Interestingly, this pattern also holds true for views between the two main minority ethnic groups, Asian British and Black British pupils: in both directions, warmer feelings result from a higher percentage of the other group in your school.

Our results also show that school ethnic composition is more important than Local Authority composition. In local authorities with high fractions of (say) Asian British pupils, White British pupils have substantially and significantly more positive feelings towards those pupils in schools where they are numerous than in schools where they are not. If the ethnic composition of local authorities is fixed, based on choices of where to live and work, then the level of ethnic segregation in schools is what matters.

Of course, this is an association between school composition and inter-group feelings. It might arise through a causal effect – that contact changes views. Or it might arise through selection – people with particular views of other groups look for schools that are more amenable to them given those views. It is not easy to tell for sure in our data, but supplementary analysis we conduct is suggestive that there is a causal force to the association.

We use data from a survey (the England sample of the CILS4EU) which provides measures of ‘warmth of feeling’ for each of the major ethnic groups towards each of the others. This is supplemented by information on friendships, attitudes to multiculturalism, and personal and school characteristics. To this we match data on school ethnic composition. Our sample offers large variation in ethnic composition (for example, from 0% Asian to 40% Asian, from 14% White to 98% White).

This issue is one that continues to resonate: the Casey Review reported in 2016 on challenges to integration. The review argued that lack of social mixing was a barrier to integration, “… where communities live separately, with fewer interactions between people from different backgrounds, mistrust, anxiety and prejudice grow.” This view harks back to communities leading ‘parallel lives’ in Cantle’s enduring term from an earlier government-commissioned review of neighbourhood relations. Encouragingly for policy-makers, our results also show that even small moves away from largely mono-ethnic schools towards more mixed ones produce positive changes. It is not the case that anything short of full integration is pointless. The policy questions then focus on how to encourage mixed schools, and how to encourage contact. Of course, neither of these are easy. But our results now quantify just how valuable that is.

Note: the report on which the above draws is available here.

This blog first appeared on the LSE British Politics and Policy blog, and can be found here: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/integrating-the-next-generation-school-composition/