Unsustainable Reliance on Land Revenues

The Chief Minister and Treasurer, Andrew Barr, in defending the dramatic increase in rates and land tax for multi-unit dwellings, is reported to have said that the higher rates will pay for services when the territory runs out of land to sell in the 2030s.

The Chief Minister’s claim raises a number of concerns. There are a range of major socio-economic implications if, as claimed by the Chief Minister, the territory runs out of land in the next ten years. To start with the ACT’s ability to meet the needs of the national government for staff, skills and services would be seriously challenged. It should be noted, however, that the taxation review panel concluded that the territory’s land holdings provide for 100 years’ of growth under an assumption of 50% supply for stand-alone dwellings.

Linking land sales to the operating revenue as the Chief Minister has done highlights the reliance of the operating budget on the sale of an asset, and essentially the unsustainability of the territory’s finances. The recently released budget includes approximately $107 million in dividend received from the two land agencies in 2019-20, increasing to $175 million in 2022-23.

An inference to be drawn from Mr Barr’s comment is that when the land runs out these revenues will be transferred to general rates. This will be a worrying thought for homeowners on low to moderate incomes, and businesses who are already struggling to meet the cost of transfer of stamp duty to their rates bills.

Canberrans not in homeownership will be equally worried. The 2019-20 budget has reduced the 4-year land supply target to 15,600 sites from 17,000 in the 2018-19 budget, the lowest since the 2014-15 budget. The reduction in supply at a time of population growth means one thing only for those seeking to buy a home or those renting – a continuing deterioration in affordability.

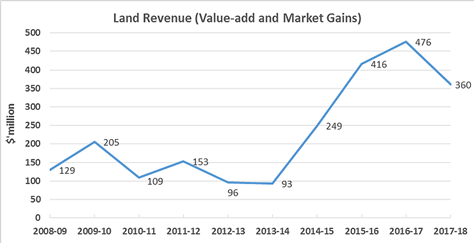

There are, of course, additional financial flows into the territory’s budget from land development activities. The financial statements apportion land revenue in three ways: undeveloped land value; value-add component; and market gains on land sales. Undeveloped land value is the payment the Suburban Land Agency (or its predecessor Land Development Agency) makes for the acquisition of raw land. Value-add component and market gains, as suggested by the names reflect benefit that could be attributed to the land agency’s development activities, and real estate agency functions in marketing englobo land and developed dwelling sites.

Revenue from land agency activities has as a consequence increased more than 500 per cent in three years from $93 million in 2013-14 to $476 million in 2016-17.

The increased revenues were not achieved through higher volumes of land sales, but by constraining supply, in particular, of single residential dwellings. The 4-year supply target was cut to just 13,500 sites in the 2014-15 budget compared to 19,500 sites in the 2012-13 budget. In 2012-13, 2,208 sites (or 51% of the supply) were for stand-alone homes. Fewer such sites were released in the following three years, with 2,089 or only 23% of the total supply being for stand-alone houses. In 2014-15, only 329 or just 9% of the dwelling sites, were for stand-alone homes. The only reasonable explanation for this reduction in supply is that it was knowingly designed to maximize revenue. It is also fair to conclude that there was no evident concern about the impact of that strategy on housing affordability.

For a small jurisdiction with a relatively less diversified economy, the ACT had been historically reliant on land revenues since self-government. Following a wide ranging review, the government committed to reducing this reliance in the 2006-07 budget as follows:

“An important element of the Government’s strategy in the 2006-07 Budget is to move the ACT away from its reliance on land sales revenue to finance the operating budget.” Noting that such a reliance was unsustainable, the government committed that “Land-based revenues will be a decreasing proportion of the overall revenues in the future.”

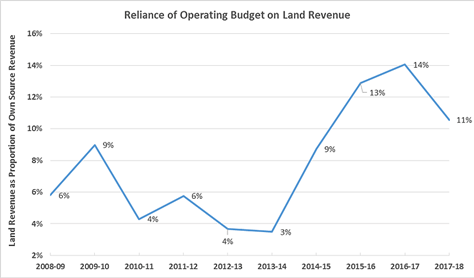

Unfortunately, early progress with that strategy has been reversed, and the territory’s budget has, in fact, become increasingly more reliant on land revenues. Land revenue as a proportion of the total territory own source revenue has increased from 3% in 2013-14 to 14% in 2016-17, and 11% in 2017-18. Such an increase in reliance on land revenue highlights problems on the revenue side of the budget which it will be difficult to address in light of the inordinate increase in taxation already imposed on households and businesses and hence their diminished capacity to pay even more.

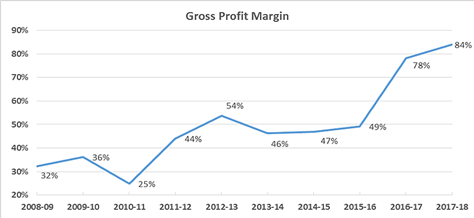

The 2019-20 forecast of gross profit margin for the Suburban Land Agency is 66%, a decrease from the estimate of 78% for 2018-19. It goes without saying that such margins would be the envy of private industry and indeed any business. Even the major banks would blush at such margins.

The budget papers claim that these margins “...are not comparable with private industry, noting that the Government, through the Suburban Land Agency, enters into the land development process at an earlier stage than a private developer. Additionally, the Government invests in infrastructure within and around its developments with the cost incurred by other Government agencies and therefore not reflected in the Suburban Land Agency’s profit margins.”

Planning processes in the lead up to land development and release and provision of infrastructure, which are core government functions, are not valid justifications for such supernormal profits. Government land development and sales activities are in competition with the private sector, and are directly comparable. In fact, the private sector has relatively higher financing costs than government and generally need higher risk margins. The government’s explanation is neither plausible nor relevant.

By comparison, according to audited annual statements, the gross profit margin in 2010-11 was 25%, which is within industry norms. This increased more than three-fold over subsequent years reaching 84% in 2017-18. These profit margins, supernormal by any measure, have been achieved through the exploitation by the ACT Government of its monopoly on land supply.

Protection of consumers from monopolistic behaviour and price gouging has been an important objective of the microeconomic reform pursued over the past few decades. In addition to enacting legislation, independent statutory bodies have been established to regulate government monopolies such as on utility services. In relation to a land supply monopoly, it is reasonable to expect that a government will not only be able to balance financial objectives against socio-economic and environmental objectives, but act in the spirit of competitive neutrality – in effect, “policy regulation”. Clearly, the ACT Government has failed to meet that expectation.