Auditor-General Should Audit Annual Budget

In February 2020, the ACT Government released its 2019-20 Budget Review[i]. The Review is a requirement of the Financial Management Act 1996, and updates the financial and economic forecasts. It takes into account events and policy decisions since the original budget was brought down, including the flow on effects of the audited results for the previous year and the Commonwealth Government’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO).

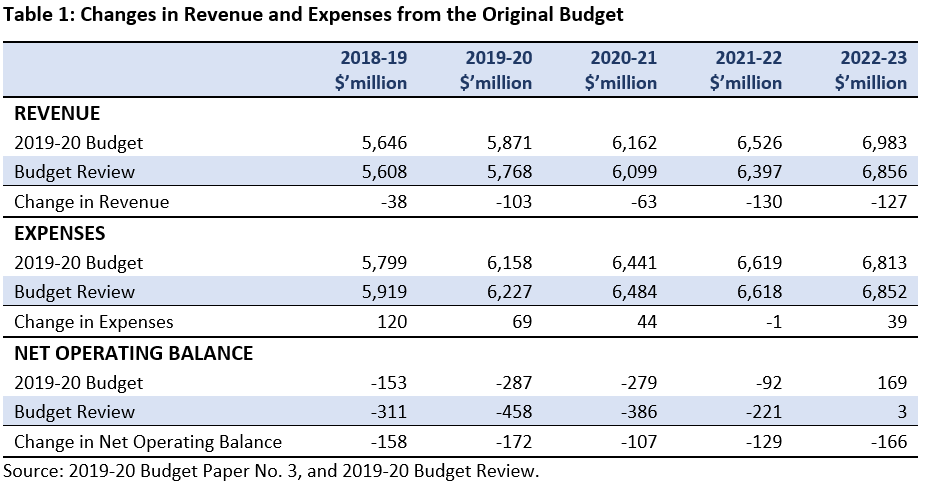

The just released Budget Review predicts an almost tripling of the operating deficit from $89.1 million to $255.6 million, on the Government’s preferred measure, namely the Headline Net Operating Balance. However the Net Operating Balance, which is the reporting framework formally agreed by all jurisdictions[ii], is now predicted to deteriorate from a deficit of $287 million in the original budget to $458 million. This represents a worsening of the deficit by $172 million from 4.7% of the operating budget to 7.4%, in just the 6 months since the presentation of the budget. Table 1 below summarizes the changes in revenue and expenses from the original budget.

Following the 2019-20 Budget, we pointed out that the revenue and expenditure trajectories in the budget were unrealistic and unsustainable[iii]. We characterized the estimates as fanciful and we were, as the record now shows, correct. Unfortunately we hold similar views about the above revised budget aggregates and do not regard them as reliable or sustainable, and in particular, we do not believe that the predicted return to a balanced budget is credible.

The Budget Review has incorporated a decrease in revenue across the budget estimates period from 2019-20 to 2022-23 which averages $90 million per annum.

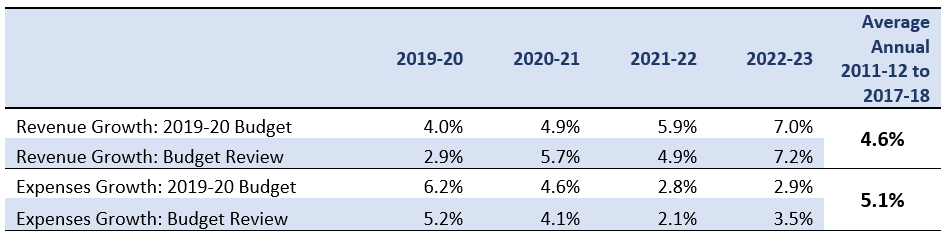

Following the publication of the original budget, we asserted that the revenue growth incorporated in the budget, which represented it as accelerating from 4% in 2019-20 to 7% in 2022-23, was unrealistic. We noted that in comparison, over the previous six years, aggregate revenue had grown by only 4.6%, during a period in which there had been significant increases in rates and levies.

On the expenditure side, the budget also implicitly included cuts that slowed spending from 6.2% growth in 2019-20 to just 2.8% and 2.9%, respectively in 2021-22 and 2022-23, compared to an average annual increase of 5.1% over the past six years. The Budget Review still reflects accelerating revenue growth above the trend, and decelerating expense growth below the trend growth. Experience suggests that these estimates should be treated with the utmost skepticism.

Table 2 below provides a comparison of the annual growth in revenue and expenses in the original budget and the Budget Review.

Notably, the return to surplus in 2022-23 is predicated on revenue growing by 7.2% in that year, and expenditure being constrained at 3.5% in that year, and just 2.1% in the preceding year. We believe these estimates can best and most politely be described as fanciful.

Notwithstanding the clear evidence that the original budget estimates were unrealistic, it is instructive to assess the reasons and justifications provided in the Budget Review for the deterioration in the budget position.

A specialist adviser’s report prepared by Pegasus Economics to assist the Legislative Assembly’s Select Committee on Estimates in its inquiry into the 2019-20 budget[iv] noted a “shrill tone” in the budget papers and political commentary unbecoming of a jurisdiction that wants to be taken seriously[v]. Unfortunately, that continues in the Budget Review detracting from the real reasons for the deterioration in the economic and financial circumstances of the Territory.

For example, in the Economic Overview, the Budget Review states[vi]:

The Commonwealth Government’s recently announced extension of the efficiency dividend on the Australian Public Service, along with any potential expansion of its decentralization program, continues to dampen Commonwealth Government expenditure in the ACT.

This is not supported by the evidence available from independent sources. The most recently released national accounts[vii] figures reveal that year-on-year to December 2019, national government expenditure (including its consumption and capital expenditures) increased by 2.9%, which was equal to the rate of increase in the ACT’s State Final Demand (SFD). On the other hand, Household Consumption in the Territory grew by just 1.7%. Remarkably, the only mention, in the Budget Review of household consumption in the Territory is on pages 11 and 14 as follows:

Household consumption has also been supported by the highest employment growth in Australia in 2019 of 3.3 per cent, with 7,500 jobs created during this period, despite subdued wages growth.

Household consumption is expected to remain solid on the back of a positive outlook for employment growth.

This begs the question why despite solid population growth and the highest employment growth in Australia, household consumption growth has remained subdued, and indeed, why the Budget Review avoids any discussion of this significant contributor to the economy[viii]. We have previously pointed out the impact of increases in rates and taxes on household budgets and their capacity for discretionary spending. An examination of the national accounts reveals that in the year to December 2019, households in the ACT spent an additional $93 million on rents and other dwelling services and $58 million on health services over the previous year in real terms.

The lack of transparency and indeed misrepresentation continues through the Budget Review, for example, in explaining the changes in the operating result. In discussing the Headline Net Operating Balance (not to be confused with the Net Operating Balance under the nationally agreed framework), it claims the “deficit increase of $166.5 million in 2019-20 primarily as a result of a decrease in GST revenue”[ix]. The true impact of the decrease in the Commonwealth grants is, however, revealed in a table and accompanying notes in the Budget Review as being only $17.6 million, which accounts for just 10% of the deterioration in the budget.

The two most significant factors contributing to the $166.5 million deterioration are: (a) on the revenue side, a drop of $51.3 million in land related revenues; and (b) on the expenditure side, policy decisions that increase expenditure by $81.6 million, of which almost $60 million relates to additional funding for ACT Health. Together, these two factors (shortfall in land revenues and increased expenditure on health) constitute 61% of the change in the budget result, and surely warrant serious discussion that is notably missing from the Budget Review.

Separately, we have highlighted the increasing reliance of the operating budget on land revenues[x] as well as the unrealistic revenue targets that have been incorporated in the budget and which the land delivery agencies have failed to deliver[xi]. The decrease in land related revenue in the Budget Review simply represents a correction to the original budget estimates, by removing revenue that on all the evidence was unlikely to be achieved.

The additional health expenditure is reported in the Budget Review under “New Initiatives” to “meet expanded activity in the health system for 2019-20, including growth in emergency department presentations and emergency surgeries”[xii]. Evidence provided by the Chief Financial Officer of the ACT Health Services to an ACT Assembly Estimates hearing revealed, however, that the Health Service would have run out of money if it did not receive a $60 million cash injection[xiii]. The reality is that the Canberra Hospital is simply not able, because of the persistent cuts it has suffered to its funding, in real terms, over many years[xiv], to meet the demands made of it by the Canberra community. As an aside ACT Health was at the point of potentially being in breach of its appropriations by the third quarter (the current quarter) of the financial year.

Notably, having addressed the funding shortfall experienced by ACT Health in 2019-20, the Budget Review does not incorporate any additional funding for Health over the forward estimates. It is, therefore, fair and reasonable to assume the starting position for the 2020-21 budget is the need for an injection into ACT Health of a minimum of at least $60 million plus allowance for growth in demand for that year. That this is the case cannot seriously be gainsaid thus, once again, bringing into question the reliability of the forward estimates.

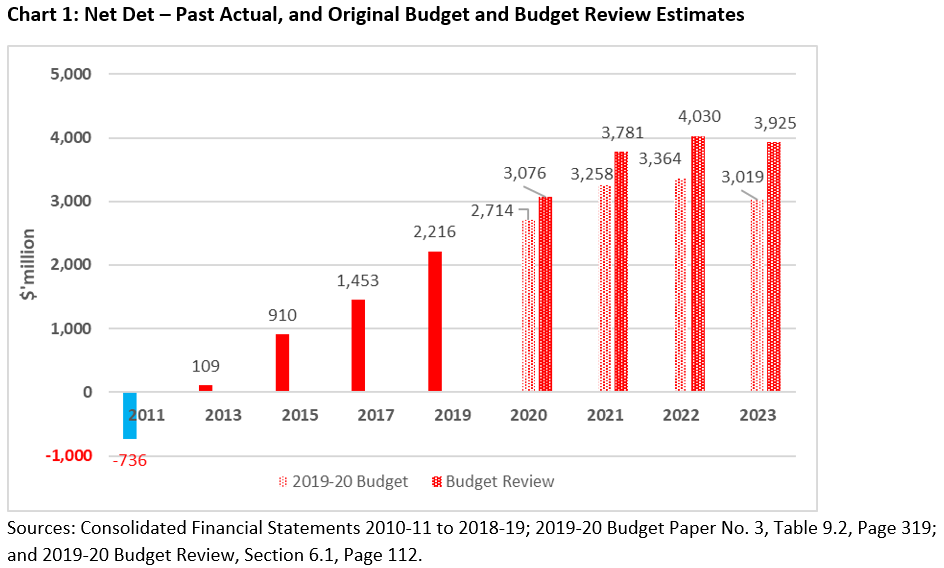

The Budget Review indicates an increase of $362 million in net debt at the end of 2019-20 from the original budget estimate of $2.714 billion to $3.075 billion. Capital initiatives committed through the Budget Review amount to $57.7 million, with the remainder of the increase in net debt resulting from a decrease in cash from operating activities.

Chart 1 below provides the trend increase from 2011, and a comparison of the original budget and Budget Review estimates.

Net debt is now forecast to peak at $4.030 billion in 2021-22, representing 63% of the operating revenue, before reducing to $3.925 billion along with a miraculous return to surplus in 2022-23.

To summarize, the changes in revenue and expenses in the Budget Review primarily are corrections to the original budget estimates. However, it is quite certain that the estimates published in the Budget Review are extremely optimistic even before taking into account the adverse impacts of the Corona virus and bushfires on the economy and revenue inflows. The balance sheet net assets also continue, in any event, to be overstated by some $3.7 billion because the 2018-19 audit flow-on of superannuation liability has not been incorporated.

Such overstatements of revenue and understatements of expenses and liabilities undermine the community’s confidence in a Government’s budgets and its ability to manage finances prudently, responsibly and in accordance with the provisions of the Financial Management Act 1996.

In view of the persistent mismatch between the presentation of the ACT budget and its underlying assumptions and the annual financial statements, there is a clear case for formally requiring that the ACT annual budget be audited by the ACT Auditor-General, and for a copy of the audit report to accompany the tabling of the budget.

In this regard it is notable that in South Australia the Auditor‑General is under a legal obligation to present a report to the House of Assembly and the State Council on the State’s public finances[xv]. Although not a complete audit, the report provides an independent and dispassionate analysis of the finances, budget estimates and forward projections and their underlying assumptions[xvi]. This is also a model that might well be considered for adoption in the ACT.

[i] ACT Government (2020); 2019-20 Budget Review, available online at https://apps.treasury.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/1479975/2019-20-budget-review.pdf.

[ii] The Net Operating Balance presented under the Uniform Presentation Framework (UPF), provides a true and fair measure of a Government’s operations. It reflects that part of an operating surplus which is related to government policy decisions and government operations, i.e., decisions over which the government has control. It excludes changes in the value of assets and liabilities resulting from market re-measurements - such as, financial investments and non-financial fixed assets - which are beyond the government’s control.

[iii] Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis Canberra Conversation Public Lecture Series (12 June 2019); The State of the ACT Budget and Its Policy Directions; https://www.governanceinstitute.edu.au/events/canberra-conversation-lecture-series/622/the-state-of-acts-budget-and-its-policy-directions.

[iv] Pegasus Economics (June 2019); Review of the ACT Budget 2019-20; available online at https://www.parliament.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1387379/Pegasus-Report-ACT-Budget-2019-Economic-FINAL.pdf.

[v] The Canberra Times (17 June 2019); 2019-20 ACT Budget labelled ‘shrill’ and too political; online at https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6220244/act-budget-shrill-and-overly-political-new-report-says/

[vi] ACT Government (2020); 2019-20 Budget Review; Section 1.1: Economic Overview, Page 12.

[vii] Australian Bureau of Statistics; ABS Cat. 5206.0, Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, Dec 2019; available online at https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/5206.0Dec 2019?OpenDocument.

[viii] National Government expenditure including consumption expenditure and gross fixed capital formation by its institutions constitutes approximately 41% of the Territory’s economy. ACT’s households’ consumption constitutes 38% of its economy.

[ix] ACT Government (2020); 2019-20 Budget Review; Section 2.1: Budget Outlook, Page 29.

[x] Stanhope J and Ahmed K; The Policy Space (September 2019); Unsustainable Reliance on Land Revenues; online at /2019/06/287-unsustainable-reliance-on-land-revenues.

[xi] Ahmed K and Stanhope J; The Policy Space (October 2019); Lessons from the 2018-19 Suburban Land Agency annual report; online at /2019/29/291-lessons-from-the-2018-19-suburban-land-agency-annual-report.

[xii] ACT Government (2020); 2019-20 Budget Review; Section 2.3: New Initiatives, Page 57.

[xiii] The Canberra Times (5 March 2020); Canberra Health Services made desperate plea for cash; online athttps://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6662914/canberra-health-services-made-a-desperate-plea-for-cash-as-staff-rationed-post-it-notes/.

[xiv] The Canberra Times (30 March 2019); The ACT government is shrinking health spending year on year; online at https://www.canberratimes.com.au/national/act/the-act-government-is-shrinking-health-spending-year-on-year-20190319-p515fd.html.

[xv] Public Finance and Audit Act 1987 (South Australia).

[xvi] See for example, Auditor‑General’s Department, South Australia (2019); Report No. 1: State Finances and Related Matters; available online at https://www.audit.sa.gov.au/publications/2019.